- Māḇōʾ hạ•Tạməṣiyṭiy

(Concise Introduction) - Nəṭiyyāh hạ•Qōmūniysəṭ,

wə•Tēʾōrəyūṯ hạ•Qəriyṭūṯ

hạ•Ḥẹḇərāṯiyūṯ

(Communist Tendency and

Critical Social Theories) - Yạhăḏūṯ, wə•Yəhūḏiy

hạ•Ḥillōniy

(Judaism and the

Secular Jew) - Dāṯ hạ•Bāhāʾiyṯ Bərẹsəlōḇiyṯ

(Breslover Bahá’í Faith) - Šôšẹlẹṯ Bərẹsəlôḇ–ʿẠkkô

(Dynasty of Breslov–Acre) - Rẹṣūʾūṯ hạ•Qōmiyqəs,

wə•hạ•Qạrəṭūniym,

wə•hạ•Qāriyqāṭūrūṯ šẹl

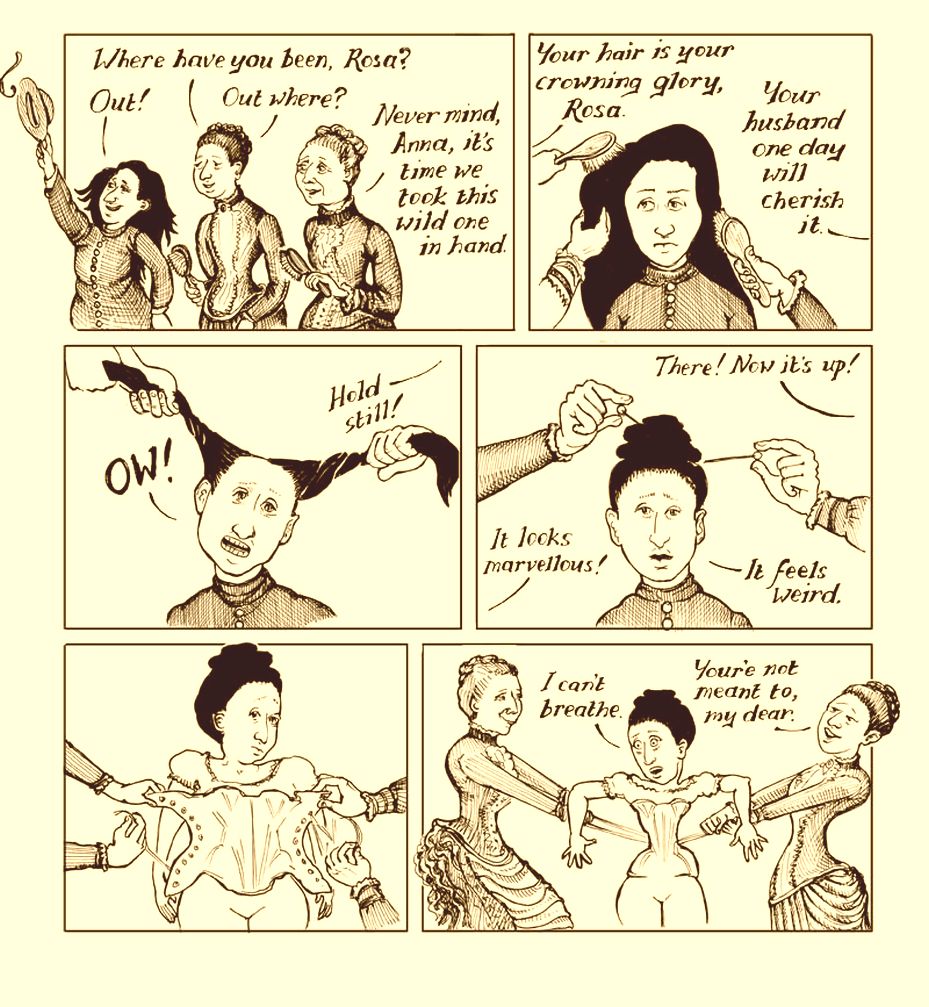

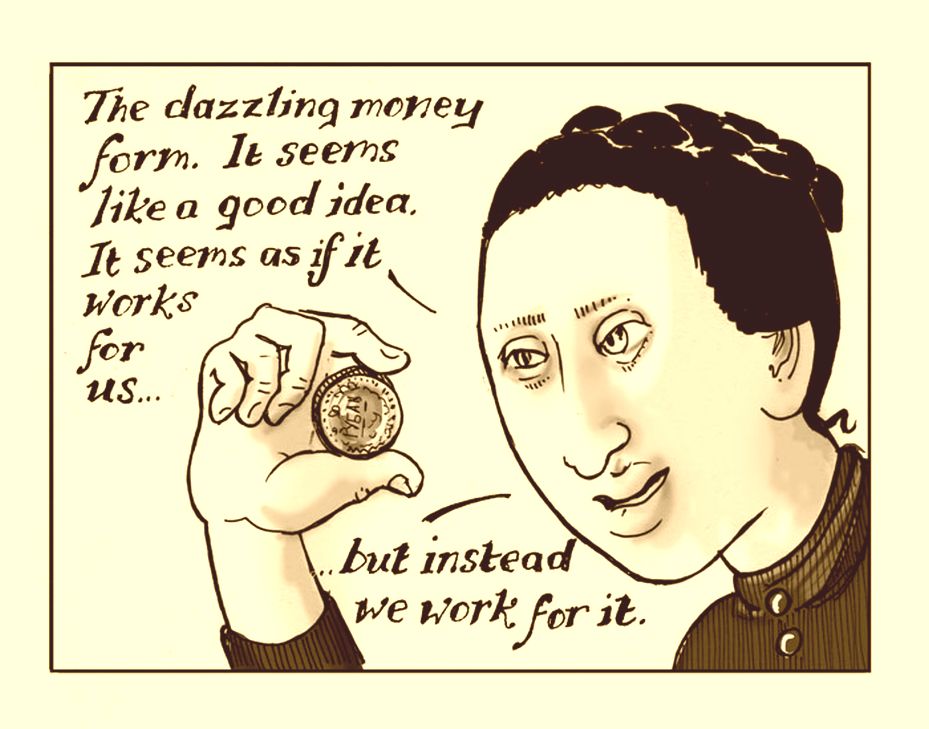

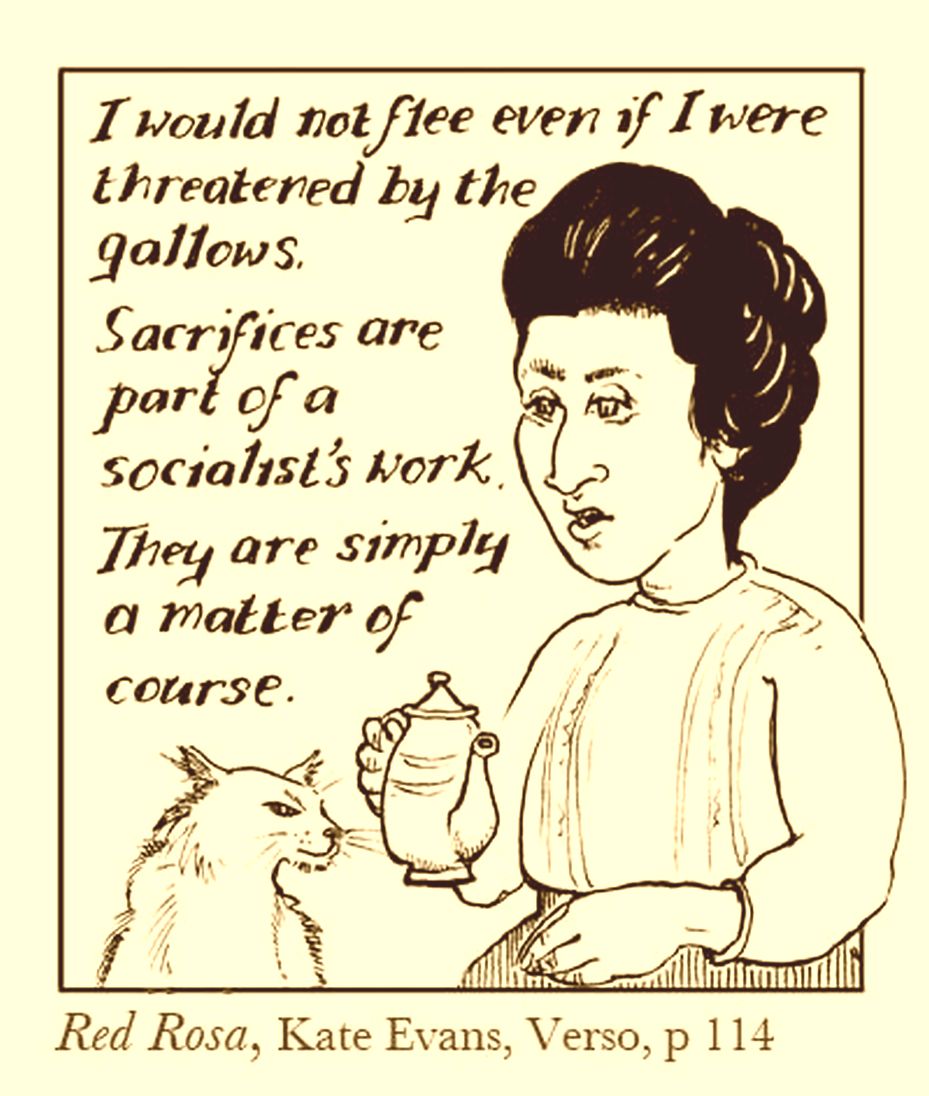

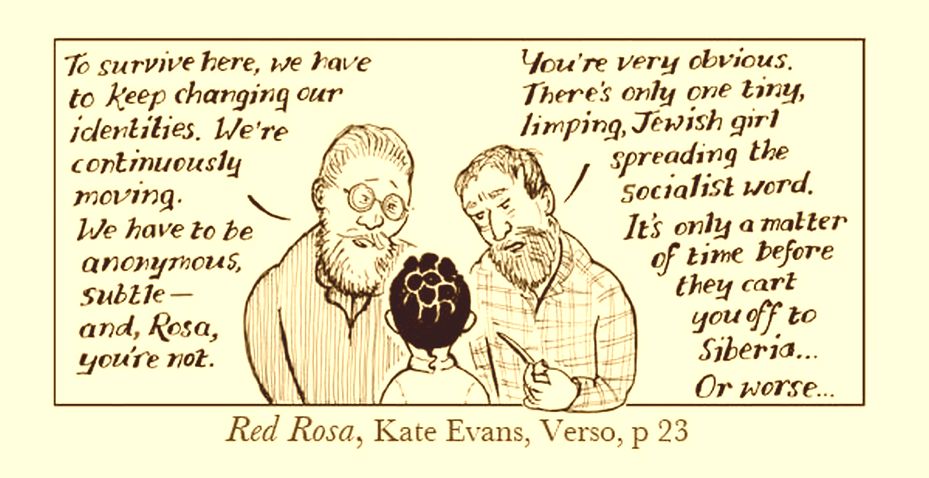

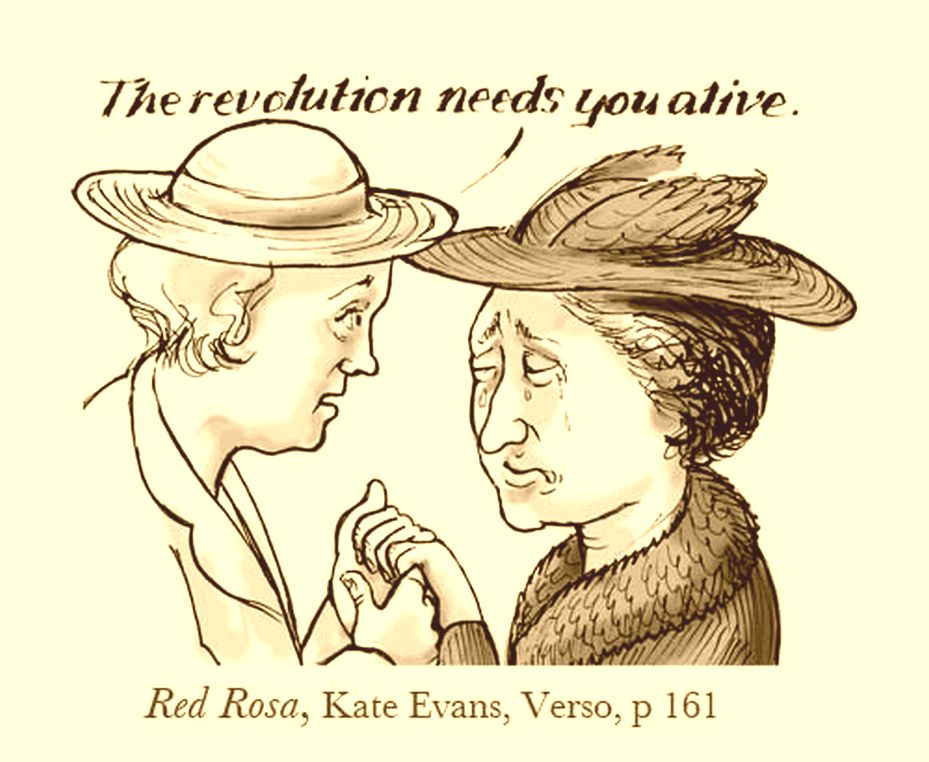

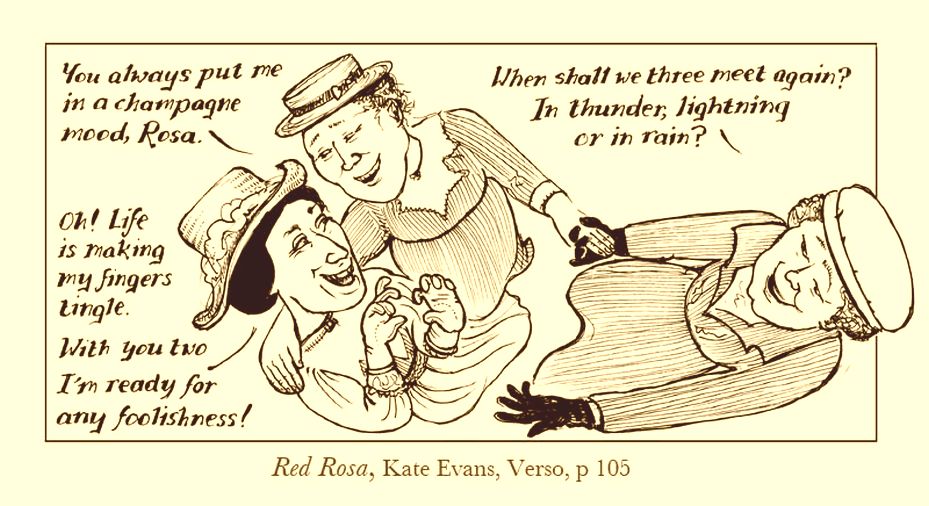

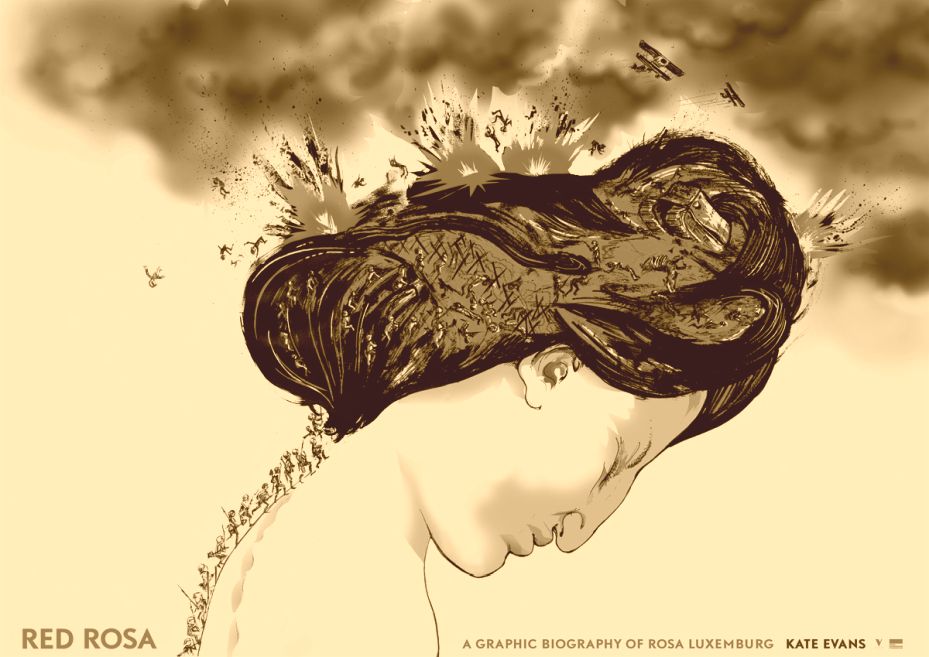

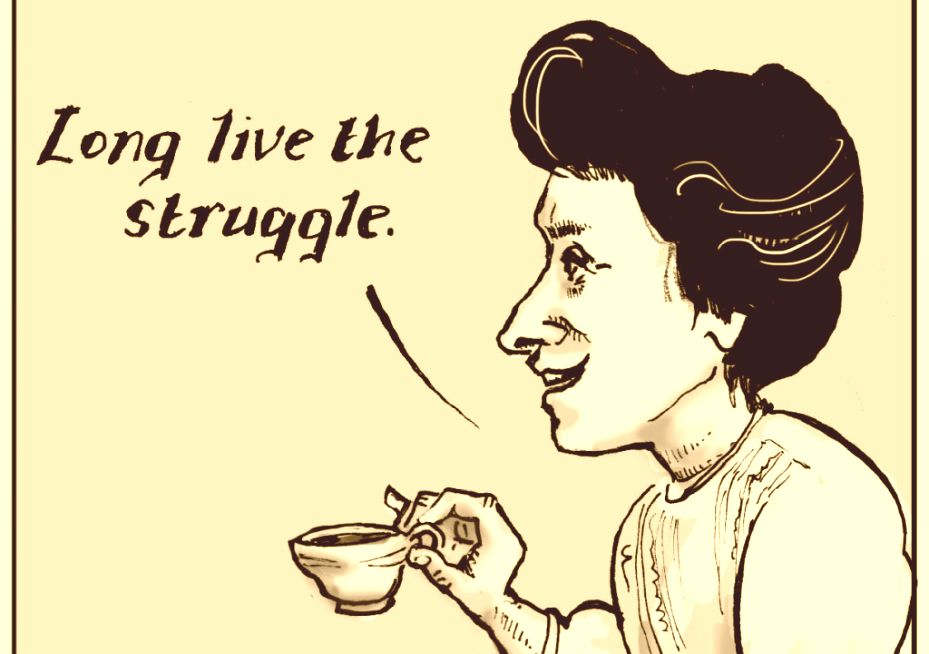

Rōzāh Lūqəsẹməbūrəg

(Comic Strips, Cartoons,

and Caricatures of

Rosa Luxemburg) - Hẹʿrōṭ lə•Siyyūm

(Concluding Remarks)

א. Māḇōʾ hạ•Tạməṣiyṭiy

א. Māḇōʾ hạ•TạməṣiyṭiyA large number of the colorized photographs featured in this monograph were transformed from the original black and white or monochrome as a courtesy of the creative developers, Oli Callaghan and Finnian Anderson, behind this Twitter bot or, if not, by Algorithmia. I am also a member of the NationStates Commonwealth (see Discord chat). In this concise introduction (Hebrew/ʿIḇəriyṯ, מָבוֹא הַתַּמְצִיתִי [MP3], māḇôʾ hạ•tạməṣiyṭiy; or Arabic/ʿArabiyyaẗ, مُقَدَّمَة المُوجَزَة [MP3], muqaddamaẗ ʾal•mūǧazaẗ), the interested reader may get a sense of the following material.

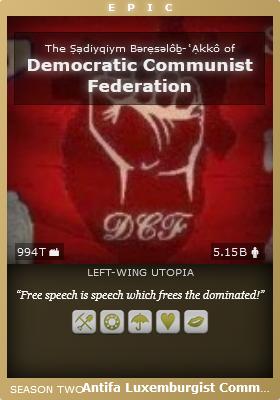

Social fiction tackles significant issues using assorted entertainment media. From a social scientific perspective, the value of social fiction should not be underestimated. The subjects addressed, sometimes hidden in metaphor, can frequently be serious and consequential. Among these genres is online gaming. As with visual and performance art, such gaming can bring to the fore topics rarely set down in other lifeworlds (German/Deutsch, Lebenswelten [MP3]). Therefore, Šôšẹlẹṯ Bərẹsəlôḇ–ʿẠkkô of Democratic Communist Federation (Spartakusland)™ (MP3) is an allegory for The Dialectical metaRealist Communist Collective™ ([MP3]; ALCC). Methodologically, the agency of governing fictional nations will be examined using ethnography (participant observation) and twin modes of phenomenological analysis (MP3]): Heartfulness Inquiry™ and The Echoing Practice™.

This monograph is an odd historical novel. The society decribed in the novel and the status or position of the writer are fictitous, but the thoughts expressed in the text, and the personal experiences, are mostly genuine. Whether the perspectives have any value is for you to decide. I would never claim to be an authority on any subject. To be perfectly honest, I distrust anyone—aside from the Prophets of God and Their legitimate successors—who makes personal claims. The novel itself is an attempt at concrete utopianism. This interesting method or approach was originally conceived by German Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch (MP3), 1885–1977. It was later developed by British Marxist philosopher and true libertarian communist Roy Bhaskar (MP3; Hindi, राम रॉय भास्कर [MP3], Rāma Rôya Bhāskara), 1944–2014. He transformed Marxism into a liberation from all absences.

Directly below, social fiction has been listed in a variety of languages using the traditional Hebrew numbering system:

- biḏəyəwôn hạ•ḥẹḇərāṯiy (Hebrew, בִּדְיְוֹן הַחֶבְרָתִי [MP3])

- ⫯adab ʾal•qaṣaṣiyy ʾal•ʾiǧ°timāʿiyy (Arabic, أَدَب القَصَصِيّ اِجْتِمَاعِيّ [MP3])

- dās°tāní•i ʾiǧ°timāʿí (Persian/Fār°sí, دَاسْتَانِیِ اِجْتِمَاعِی [MP3])

- doston•i iǧtimoī (Tajik/Toǧikī, достони иҷтимоӣ [MP3])

- samāǧí ʾaf°sānih (Urdu/ʾUr°dū, سَمَاجِی افْسَانِہ [MP3])

- samājika galapa (Guramukhi Punjabi/Guramukhī Pajābī, ਸਮਾਜਿਕ ਗਲਪ [MP3])

- samāǧika galapa (Shahmukhi Punjabi/Šāha Muḱ°hí Pan°ǧābí, سَمَاجِکَ گَلَپَ [MP3])

- samāǧī ʾaf°sān°wī (Sindhi/Sin°dʱī, سَمَاجِي افْسَانْوِي [MP3])

- ʾiǧ°timāʿí ʾaf°sānih (Pashto/Paṣ̌°tū/Pax̌°tū, اِجْتِمَاعِی افسَانِه [MP3])

Return to the Page Menu.

ב. Nəṭiyyāh hạ•Qōmūniysəṭ,

ב. Nəṭiyyāh hạ•Qōmūniysəṭ,

wə•Tēʾōrəyūṯ hạ•Qəriyṭūṯ

hạ•Ḥẹḇərāṯiyūṯ

In this chapter, I shall discuss, only in their basic elements, my personal communist tendency and critical social theories (Hebrew, נְטִיָּה הַקוֹמוּנִיסְט, וְתֵּאוֹרְיוּת הַקְרִיטוּת הַחֶבְרָתִיוּת [MP3], nəṭiyyāh hạ•qômūniysəṭ, wə•tēʾōrəyūṯ hạ•qəriyṭūṯ hạ•ḥẹḇərāṯiyūṯ; or Arabic, اِتِّجاه الشُيُوعِيّ، وَنَظَرِيَّت الاِجْتِمَاعِيَّة النَقْدِيَّة [MP3], ʾittiǧah ʾal•šuyūʿiyy, wa•nazariyyaẗ ʾal•iǧ°timāʿiyyaẗ ʾal•naq°diyyaẗ) and, when taken as a whole, my more generalized heterodoxy (Hebrew, הֶטֶרוֹדּוֹקְסִי [MP3], hẹṭẹrôdōqəsiy; Arabic, اِبْتِدَاع [MP3], ʾib°tidāʿ; Persian, زَنْدَقِه [MP3], zan°daqih; Urdu, ہِجْرَت [MP3], hiǧ°rat; Guramukhi Punjabi, ਹੈਟਰੋਡੌਸੀ [MP3], haiṭarōḍausī; Shahmukhi Punjabi, ہَیٹَرُوڈَوسِی [MP3], haý°ṭarūḍaw°sí; Hindi/Hiṃdī, विधर्म [MP3], vidharma; or Bengali/Bāṅāli/Bānlā, বৈধর্ম্য [MP3], baidharmya), or holding to a contrary perspective from the norm. Freedom of thought is required by libertarian communism.

Šạbāṯ hạ•niṣəḥiyṯ ššālôm! (Hebrew, שַׁבָּת הַנִצְחִית שָּלוֹם!, “peace of the eternal Sabbath!”) Indeed, heterodoxy can be a valued trait so long as it is attended to by the equally valued trait, presented here multilingually, of engaging in correct action or, technically, orthopraxy:

- ʾôrəṯ′ôpərāqəsiy (Hebrew, אוֹרְת׳וֹפּרָקְסִי [MP3])

- sulūk ʾal•ṣaḥīḥ (Arabic, سُلُوك الصَحِيح [MP3])

- durus°t•i ḱar°dārí (Persian, دُرُسْتِ کَرْدَارِی [MP3])

- ʾur°tūp°raḱ°sí (Persian, اُرْتُوپْرَاکْسِی [MP3])

- amalho•i durust (Tajik, амалҳои дуруст [MP3])

- sim ʿamal (Pashto, سِم عَمَل [MP3])

- durus°ta ʿamala (Urdu, دُرُسْتَ عَمَلَ [MP3])

- ṣaḥīḥ ʿamal (Sindhi, صَحِيح عَمَل [MP3])

- sahī kāravāꞌī (Guramukhi Punjabi, ਸਹੀ ਕਾਰਵਾਈ [MP3])

- ṣaḥí ḱāravā⫯yí (Shahmukhi Punjabi, صَحِی کَارَوَائِی [MP3])

- sahī kārravāī (Hindi, सही कार्रवाई [MP3])

- saṭhika padakṣēpa (Bengali, সঠিক পদক্ষেপ [MP3])

The Left, as a diverse spectrum, should, I believe, be defined as communism or revolutionary socialism. Other left–of–center standpoints may be termed left–wing. Libertarian socialism, and the entire Left, can be situated into three broad, even if not mutually exclusive, rubrics. Overlaps could be pinpointed between perspectives within one category and those within the additional two. The three schools of the Left are Marxism, anarchism, and poststructuralism (a contested term). Marxism, including revolutionary syndicalism, centers upon Karl Marx (MP3), 1818–1883, and Friedrich Engels (MP3), 1820–1895. Anarchism, a fragmented tradition, lacks generally agreed–upon founders. The poststructural influences on communism, as seen in postautonomism and postanarchism, originated with Michel Foucault (MP3), 1926–1884; Jacques Derrida (MP3), 1930–2004; and others.

Click on the Libertarian Marxist Tendency Map to Enlarge

For left regroupment or unity, the vehicle driven, while traveling through many hazardous thoroughfares toward a new and unified Left, is the tendency, which was developed by the writer, of Antifa Luxemburgism™ (MP3). Since that tendency has already been considered in greater depth on a dedicated website, most of the discussions within this monograph will be fairly general and brief. Here are translations of the term, Antifa Luxemburgism, into fifteen languages:

- Hebrew, לוּקְסֶמְבּוּרְגִּיוּת הַאַנְטִיפָשִׁיסְטית (MP3), Lūqəsẹməbūrəgiyūṯ hạ•ʾạnəṭiyp̄āšiysəṭiyṯ.

- Arabic, لُوكْسِمْبُورْغِيَّة مُضَادّ الفَاشِيَّة (MP3), Lūk°sim°būr°ġiyyaẗ muḍādd ʾal•fāšiyyaẗ.

- Persian, لُوکْسِمْبُورْگِیَه ضِد فَاشِیَه (MP3), Lūḱ°sim°būr°giýah ḍid fāšiýah.

- Tajik, Люксембургизм зидди фашизм (MP3), Lyuksemburgizm ziddi fašizm.

- Pashto, دَ نَظَرَه دَ انْټِیفَا او لُوکْزَامْبُورْګ (MP3), Da Naẓarah da ʾAn°ṭífā ʾaw Lūḱ°zām°būr°ǵ.

- Urdu, لُوْكسِمْبُرْگِیَّتَ مُخَالِفَ ـ فَاشِیَّتَ (MP3), Lūk°sim°bur°giýýata muẖālifa–fāšiýýata.

- Bengali, বিরোধী–ফ্যাসিবাদী লুক্সেমবুর্গবাদ (MP3), birōdhī–phyāsibādī Luksēmaburgabāda.

- Hindi, फ़ासिस्ट–विरोधी लक्समबर्गवाद (MP3), fāsisṭa–virodhī Laksamabargavāda.

- Guramukhi Punjabi, ਵਿਰੋਧੀ–ਫਾਸ਼ੀਵਾਦੀ ਲਕੇਸਮਬਰਗਵਾਦ (MP3), virōdhī–phāsīvādī Luksēmaburagavāda.

- Shahmukhi Punjabi, وِرُودْهِی ـ فَاسِیوَادِی لُکْسَیمَبُرَگَوَادَ (MP3), virūd°hí–fāsívādí Luḱ°sēmaburagavāda.

- Malayalam/Malayaḷaṃ, ഫാസിസ്റ്റ്–വിരുദ്ധ ലുകസമബുരഗിസം (MP3), phāsisṟṟ–virudꞌdha Lukasamaburagisaṁ.

- Sinhalese/Siṁhala, ෆැසිස්ට්–විරෝධී ලක්ෂම්බර්ග්වාදය (MP3), fæsisṭ–virōdhī Lakṣambargvādaya.

- Turkish/Türk Dılı, zit–faşist Luxemburgizm (MP3).

- Modern Greek/Néa Ellēniká, αντιφασιστικό Λουξεμβούργμός (MP3), antiphasistikó Louxemboúrgmós.

- Sindhi, مُخَالِف ـ فَاشِسْٽ لُوڪْسِيمْبُورْگِزْم (MP3), muẖālif–fāšis°ʈ Lūk̀°sīm°būr°giz°m.

A “turn” (Hebrew, תַּפְנִית [MP3], tạp̄əniyṯ; Arabic, تَحَوُّل [MP3], taḥawwul; or Persian, نُوبَت [MP3], nūbat; Urdu, مَوْڑَ [MP3], maw°ṛa; Guramukhi Punjabi, ਮੋੜ [MP3], mōṛa; Shahmukhi Punjabi, مُوڑَ [MP3], mūṛa; or Tajik, хамгашт [MP3], ẖamgašt) is a commonly utilized academic term for a profoundly significant shift, or even an absolute transformation in some cases, to one’s mindset or worldview (German, Weltanschauung [MP3] or Weltansicht [MP3]). Many theoretical or philosophical turns fill my memory. I have, as a lifelong committed Leftist, made turns to a mélange (MP3) of communist tendencies or currents. Some of them, I must admit, were more personally beneficial, in the process of awakening my consciousness of capitalist intersectionality, than others. Still, throughout all these turns, I remained, for the most part, a left–libertarian or libertarian communist:

- the U.S. New Left’s left–libertarianism through the Students’ Democratic Coalition (1968–1969), open to secondary as well as to college and university students.

- Titoism (MP3; Serbian/Srpski, Титоизам [MP3], Titoizam; Hebrew, טִיטוֹאִית [MP3], Ṭiyṭôʾiyṯ; Hebrew, טִיטוֹאִיזְם [MP3], Ṭiyṭôʾiyzəm; Arabic, تِيتُوِيَّة [MP3], Tītuwiyyaẗ; Ṭiyṭōʾiyzəm; Persian, تِیتُوِیسْم [MP3], Títuwís°m; Urdu, ٹِیٹُوَنَے [MP3], Ṭíṭuwanē; Guramukhi Punjabi, ਟਿਟੋਵਾਦ [MP3], Ṭiṭōvāda; Shahmukhi Punjabi, ٹِٹُووَادَ [MP3], Ṭiṭōvāda; Sindhi, ٽَائْٽُوِزْم [MP3], Ʈā⫯y°ʈuwiz°m; Hindi, टीटोवाद [MP3], Ṭīṭovāda; or Bengali, টিটোবাদ [MP3], Ṭīṭōbāda).

- the post–Maoist (MP3) left–refoundational Maoism of Freedom Road Socialist Organization (Left Refoundation).

- the post–Trotskyist (MP3) Solidarity (U.S.) of left–refoundation and left–regroupment.

- the post–Maoist Third–World Maoism (Hebrew, מָאוֹאִיזְם בְּעוֹלָם הַשְׁלִישִׁי [MP3], Māʾôʾiyzəm bə•Ôlām hạ•Šəliyšiy; (Arabic, مَاوِيَّة مِن العَالَم الثَالِث [MP3], Mawiyyaẗ min ʾal•ʿĀlam ʾal•Ṯāliṯ; Persian, مَائُوئِیسْمِ جَهَان سِوُّم [MP3], Mā⫯ū⫯yís°m•i Ǧahān Sivvum; Urdu, تِیسْرَا دِنِیَا مَاؤُوِزْمَ [MP3], Tís°rā Diniyā Mā⫯wuwiz°ma; Guramukhi Punjabi, ਤੀਸਰਾ ਸੰਸਾਰ ਮੌਸਮ [MP3], Tīsarā Sasāra Mausama; Shahmukhi Punjabi, تِیسَرَا سَسَارَ مَوْسَمَ [MP3], Tísarā Sasāra Maw°sama; Mandarin Chinese, 第三世界的毛主义 [MP3], Dì•Sān•Shìjiè•de•Máo•Chǔyì; or Cantonese Chinese/Gwong2•Dung1•Waa6, 第三世界毛澤東思想 [MP3], Dai6•Saam1•Sai3•Gaai3•Mou4•Zaak6•Dung1•Si1•Soeng2). Given that my current views of this tendency are mostly on the negative side, my brief attraction to the current is, even for me, difficult to fully understand. I was, to be honest, drawn to Third–World Maoism out of empathy for the impact of Western capitalism and imperialism on developing or Third World countries. Still, I only “dabbled” in the tendency for about two or three weeks. As quickly as I accepted the current, I was turned off from it. In other words, I rejected the view that the global revolution must begin in the Third World. Contrary to the common thinking of Third–World Maoists, the dialectic is international. No one can predict where revolution will start. The U.S. itself is ripe for revolution. However, instead of a revolution, much of the socially alienated Proletariat chose a capitalist, Donald Trump. A common Third–World Maoist question is, Why has revolution not occurred in the West? Well, my response to the question is, Why has it not occurred anywhere? I obviously do not know whether Trump will be re–elected. However, in my view, he will remain president for as long as it takes to destroy the capitalist world–system, including the Empire or U.S.

- the post–Trotskyist international socialism (Hebrew, סוֹצְיָאלִיזְם הַבֵּינְלְאֻמִּי [MP3], sôṣəyāʾliyzəm hạ•bēynələʾumiy; Arabic, اِشْتِرَاكِيَّة الدَوْلِيَّة [MP3], ʾiš°tirākiyyaẗ ʾal•daw°liyyaẗ; Persian سُوسِیَالِیسْمِ بِینَالْمِلَلِی [MP3], sūsiýālís°m•i baýnāl°milalí; Urdu, بَیْنٍ اُلاقْوَامِی سُوسِهِلِزمَ [MP3], baý°na ʾul•ʾaq°wāmí sūsihiliz°ma; Guramukhi Punjabi, ਅੰਤਰਰਾਸ਼ਟਰੀ ਸਮਾਜਵਾਦ [MP3], atararāśaṭarī samājavāda; or Shahmukhi Punjabi, انْتَرَرَاشَٹَرِی سَمَاجَوَادَ [MP3], ʾan°tararāšaṭarí samaǧavāda) of International Socialist Tendency, Counterfire, International Socialist Network (IS Network), Socialist Solidarity (Canada), The International Socialist Organization (ISO), New Socialist Group, Socialist Alternative (Australia), rs21: revolutionary socialism in the 21ˢᵗ century, and Left Unity.

- the neo–Trotskyist (MP3) third–camp socialism (Hebrew, סוֹצְיָאלִיזְם שֶׁל הַמַחֲנֶה הַשְׁלִישִׁי [MP3], sôṣəyāʾliyzẹm šẹl hạ•mạḥănẹh hạ•šẹliyšiy; Arabic, اِشْتِرَاكِيَّة الثَالِثَة لِلمُخَيَّم [MP3], ʾiš°tirākiyyaẗ ʾal•ṯāliṯaẗ lil•muẖayyam; Persian, سُوسِیَالِیسْمِ سِوُّمِ ارْدُوگَاه [MP3], sūsiýālís°m•i sivvum•i ʾar°dūgāh; Urdu, تِیسْرِی چْھَاؤْنِی اجِتَمَاعیَاتَ [MP3], tír°sí č°hā⫯w°ní ʾaǧitamāʿýāta; Guramukhi Punjabi, ਤੀਜੇ ਡੇਰੇ ਸਮਾਜਵਾਦ [MP3], tījē ḍērē samājavāda; or Shahmukhi Punjabi, تِیجْے ڈَیرَے سَمَاجَوَادَ [MP3], tīǧē ḍērē samāǧavāda) of the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty. I remain a Trotskyist (really, post–Trotskyist and neo–Trotskyist), and my interest in Trotskyism (Hebrew, טְרוֹצְקִיִיזְם [MP3], Ṭərôṣəsəqiyiyzəm; Arabic, تْرُوتْسْكِيِيَّة [MP3], T°rūt°s°kiyiyyaẗ; Persian, تْرُوتْسْکِیِیسْم [MP3], T°rūt°s°ḱiýís°m; Urdu, ٹْرَاٹْسْکِیِزمَ [MP3], Ṭ°rāṭ°s°ḱiýíz°ma; Guramukhi Punjabi, ਟ੍ਰਾਟਸਕੀਵਾਦ [MP3], Ṭrāṭasakīvāda; Shahmukhi Punjabi, ٹ°رَاٹَسَکِیوَادَ [MP3], Ṭ°rāṭasaḱívāda; Hindi, ट्रॉट्रस्कीवाद [MP3], Ṭrôṭraskīvāda, ट्राटस्किवाद [MP3], Ṭrāṭaskivāda, or ट्रॉट्स्काइयिज़म [MP3], Ṭrôṭskāiyizama; Bengali, ট্রটস্কীবাদ [MP3], Ṭraṭaskībāda; or Malayalam, ട്രോട്സ്കിസം [MP3], Ṭrēāṭskisaṁ) has only intensified.

- nearly rebounding full circle to the third–camp Marxism, left–libertarian Luxemburgism (MP3), and left–libertarian Antifa (MP3) I so deeply cherish.

To conclude the basics, the prerequisite for left regroupment is left refoundation or renewal. Throughout my long life, each of the rubrics which will be considered in this chapter have, as refoundation, been combined into The Institute for Dialectical metaRealism™ (MP3), The Collective to Fight Neurelitism™ (MP3), and ALCC. My model of left refoundation is the Libertarian Communist Pentad™ (Hebrew, חֲמִישִׁיָּה שֶׁל הַקוֹמוּנִיזְם הַחֵרוּת [MP3], ḥămiyšiyāh šẹl hạ•qômūniyzəm hạ•ḥērūṯ) of Dialectical metaRealism™. Five perspectives, all revolving around Bhaskar’s critical realism, have been woven into a tapestry through this pentad of left–libertarian, or anti–authoritarian, communism:

- ʾạḥəḏūṭ hạ•šẹmāʾliyṭ (Hebrew, אַחְדוּת הַשְׂמָאלִית [MP3]), “left regroupment or unity”

- wifāq ʾal•yasār (Arabic, وِفَاق اليَسَار [MP3]), “left regroupment or unity”

- ⫰iʿādaẗ ʾal•taǧ°mīʿ ʾal•yasār (Arabic, إِعَادَة التَجْمِيع اليَسَار [MP3]), “left regroupment or unity”

- vaḥ°dat•i čap (Persian, وَحْدَتِ چَپ [MP3]), “left regroupment or unity”

- yagonagi•i čap (Tajik, ягонагии чап [MP3]), “left regroupment or unity”

- bā⫯yiýṉ ʾittiḥāda (Urdu, بَائِیں اِتِْحَادَ [MP3]), “left regroupment or unity”

- khabē ēkatā (Guramukhi Punjabi, ਖੱਬੇ ਏਕਤਾ [MP3]), “left regroupment or unity”

- ḱ°habē ʾaý°ḱatā (Shahmukhi Punjabi, کْھَبَے ایْکَتَا [MP3]), “left regroupment or unity”

- ḥidūš hạ•šẹmōʾl (Hebrew, חִדּוּשׁ הַשְׂמֹאל [MP3]), “left refoundation or renewal”

- taǧ°dīd ʾal•yasār (Arabic, تَجْدِيد اليَسَار [MP3]), “left refoundation or renewal”

- ⫰iʿādaẗ ʾal•t⫯āsīs ʾal•yasār (Arabic, إِعَادَة التَأْسِيس اليَسَار [MP3]), “left refoundation or renewal”

- taǧ°díd•i čap (Persian, تَجْدِیدِ چَپ [MP3]), “left refoundation or renewal”

- navkunī•i čap (Tajik, навкунӣи чап [MP3]), “left refoundation or renewal”

- bā⫯yiýṉ taǧ°dída (Urdu, بَائِیں تَجْدِیدَ [MP3]), “left refoundation or renewal”

- khabē navīnīkarana (Guramukhi Punjabi, ਖੱਬੇ ਨਵੀਨੀਕਰਨ [MP3]), “left refoundation or renewal”

- ḱ°habē navíníḱarana (Shahmukhi Punjabi, کْھَبَے نَوِینِیکَرَنَ [MP3]), “left refoundation or renewal”

Borrowing a term used in my Master’s thesis from 1980, Increasing Complexity as a Process in Social Evolution: A Case Study of the Bahá’í Faith, capitalism is a complexification. Briefly, the name Dialectical metaRealism comes from Bhaskar’s work. The term is a portmanteau of his dialectical critical realism and his philosophy of metaReality. The result is a play on words or, if you prefer, a pun. Obviously, Dialectical metaRealism sounds a great deal like dialectical materialism. Practically speaking, Dialectical metaRealism, while lovingly and respectfully adopting Bhaskar’s work as its metatheoretical and methodological foundation, uses Antifa Luxemburgism, as developed by this writer, for its communist tendency. In addition, a wide variety of other critical social theories, many of them briefly discussed in this chapter, have been incorporated into Dialectical metaRealism.

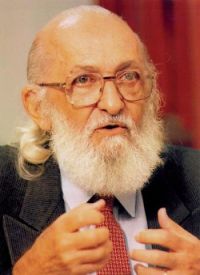

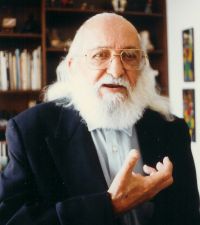

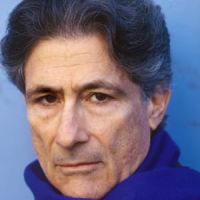

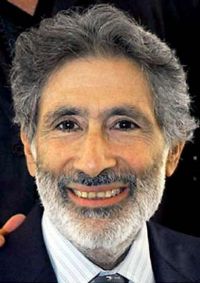

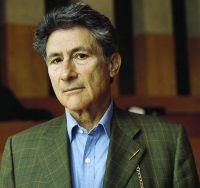

In this Marxist–Luxemburgist (MP3) project of left refoundation, the pentad remains at the midpoint, and Bhaskarian critical realism has been positioned squarely at the center of the pentad. The project draws upon a multitude of critical frameworks and the activities of their scholars and practitioners. Of particular importance to the long–term process of formulating my perspective has been a continued personal phenomenological reflection on the work conducted by each of the individuals listed directly below, especially the dearly loved Rosa Luxemburg and the brilliant Roy Bhaskar:

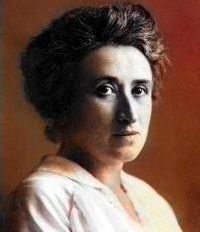

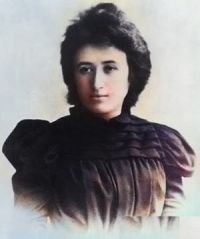

- Rosa Luxemburg ([German; MP3]; Róża Luksemburg [Polish/Polski; MP3]; Róży Luksemburg [Polish; [MP3]; Rôzạh bạṯ ʾĔliyyāhū [Hebrew, רוֹזַה בַּת אֱלִיָּהוּ; MP3]; Rʾọsʾạ bạṯ ʾĔliyyāhū [Yiddish/Yiyḏiyš, ראָסאַ בַת אֱלִיָּהוּ; MP3]; Rūzaẗ ʾib°naẗ ⫰Iy°liyā [Arabic, رُوزَة اِبْنَة إِيْلِيَا; MP3]; Rūzā duẖ°tar•i ʾIl°ýās [Persian, رُوزَا دُخْتَرِ اِلْیَاس; MP3]; Roza duẖtar•i Ilyos [Tajik, Роза духтари Илёс; MP3]; ʾIý°laýāh ḱí Bēṭí ḱā Rūzā

[Urdu, اِیْلَیَا کِی بَیٹِی کَا رُوزَا; MP3]; Ēlīyāha dī dhī Rōzā [Guramukhi Punjabi, ਏਲੀਯਾਹ ਦੀ ਧੀ ਰੋਜ਼ਾ; MP3]; or ʾAý°líýāha, i.e., ʾĒ°līýāha, dí d°hí Rūzā [Shahmukhi Punjabi, اَیْلِییَاہَ دِی دْھِی رُوزَہ; MP3]), 1871–1919, is the central figure and saintly being of Spartakusland (MP3)—a common alias for the Federation and the name of its capital city—and The Antifa–Luxemburgist Communist Collective. Dear Rosa Luxemburg had the nickname of Red Rosa

([German, rote Rosa [MP3]; or Polish, rudy Rosa [MP3]). She was born to Eliasz (Polish for Elijah; MP3) and Liny (Polish; MP3) on March 5ᵗʰ, 1871, in Zamość (Polish [MP3]), Zāʾmŏʾšəṭəś (Yiddish, זָאמֳאשְׁטְשׂ [MP3]), or Zāmôšəṣ′ (Hebrew, זָמוֹשְׁץ׳ [MP3]), Poland (Polish, Polska [MP3]). Rosa was a naturalized German citizen, a libertarian Marxist, a proto–left communist, a doctor of law, and a nonobservant Jew. At only 48 years of age, she then became a secular martyr, after being assassinated by rifle, in Berlin, Germany, on January 15ᵗʰ, 1919. In that very same year, my Jewish father was born—eight months nine days later—on September 24ᵗʰ, 1919, in Brooklyn, New York. Since I was born on February 27ᵗʰ, 1956, Rosa was old enough to be my great grandmother and then some. However, setting that aside, as if she were my wedded wife, I am deeply in love with her. I have, by the same token, happily been a life–long bachelor.

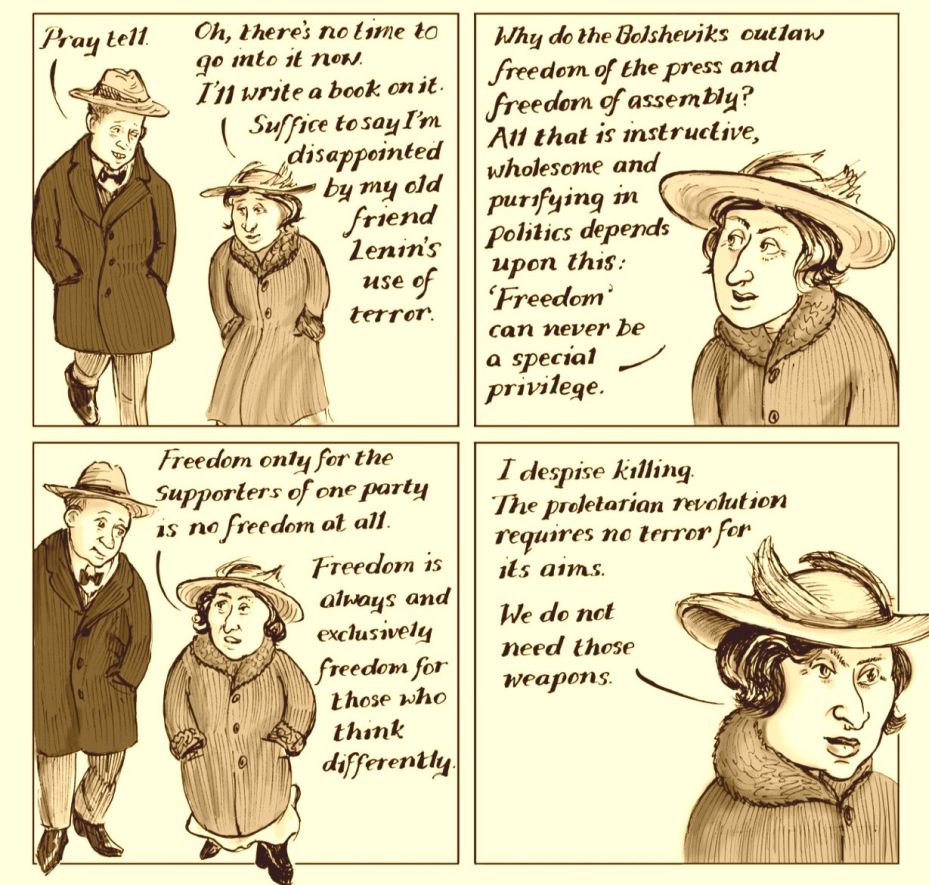

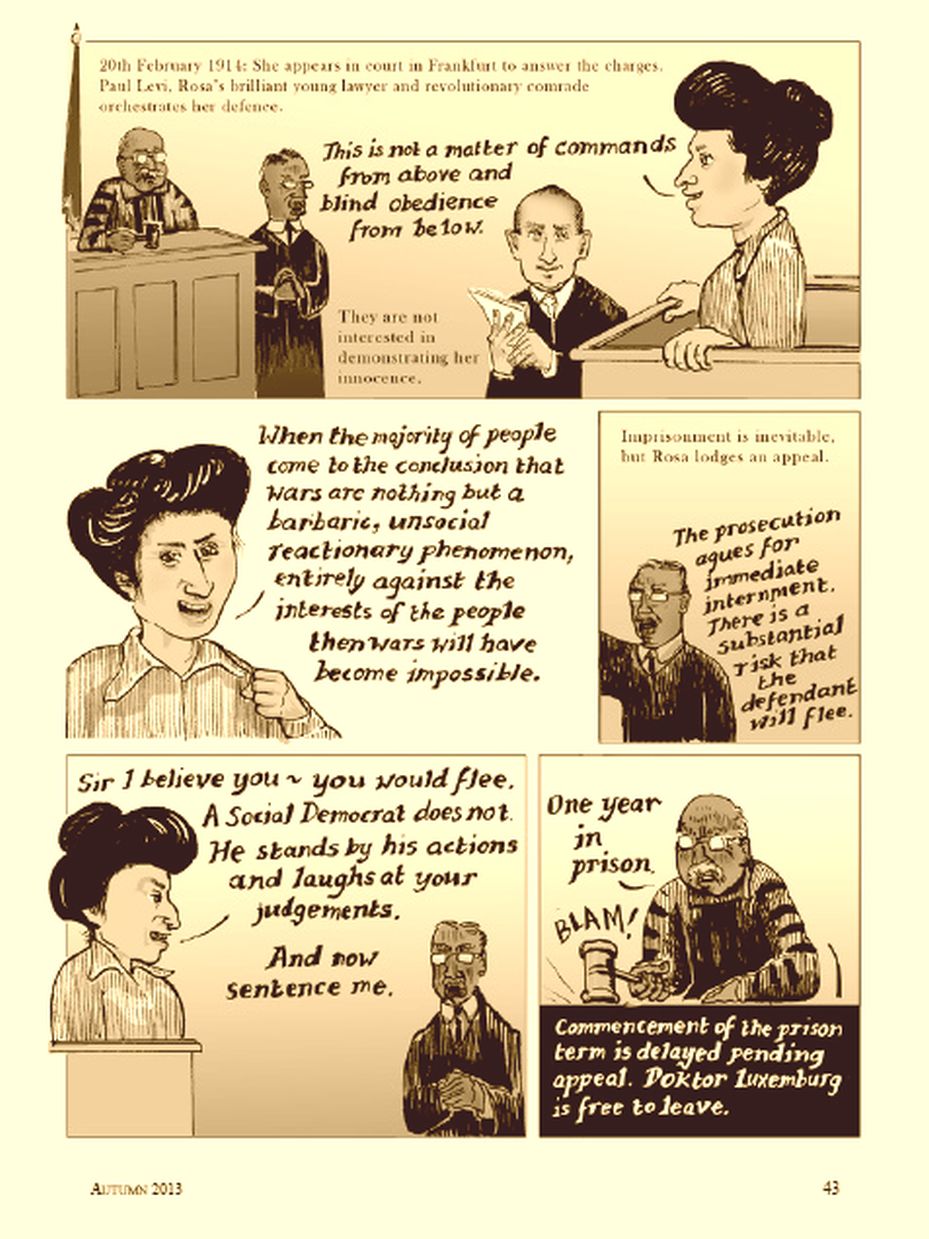

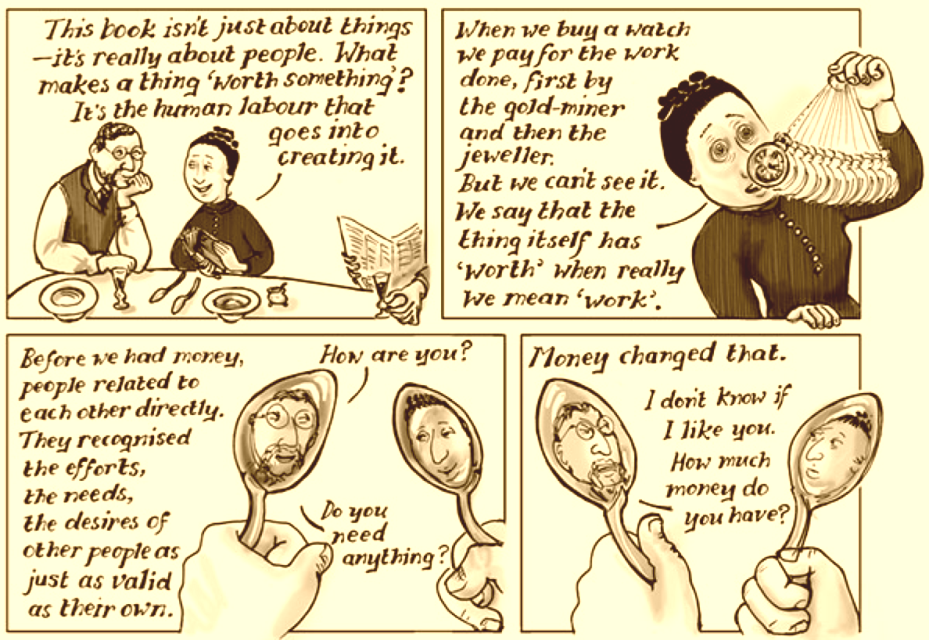

Taking Rosa, the beloved heroine residing eternally in my heart, as exemplar, work heartily, with the spirit of genuine revolutionary fervor, for democratic libertarian communism. Rosa spent hours upon hours working through Capital and other works. She did not treat Marxist primary sources as verbally inerrant (Hebrew, מוּשְׁלָמוּת מִלּוּלִית [MP3], mūšəlāmūṯ millūliyṯ; or Arabic, مَعْصُوم لَفْظِيّاً [MP3], maʿ°ṣūm laf°ẓiyāṇ) or as manna (Hebrew, מָן [MP3], mān; Arabic, مَنّ [MP3], mann; or Common Greek/Hellēniká Koinḗ, μάννα [MP3], mánna, “what is it?”) from heaven. Instead, she approached these sources with the trained mind of a legal scholar. In point of fact, Rosa was one of the few women of her generation with an earned terminal German doctorate in law. That degree is generally considered as higher in prestige than the American Doctor of Jurisprudence (J.D.) degree. In 1963, the J.D. officially supplanted the Bachelor of Laws (LL.B.), which was, quite oddly using U.S. criteria, a second baccalaureate awarded after attaining the Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) or Bachelor of Science (B.S.). The German doctorate is seemingly on par, not with the J.D. or even with the intermediate American Master of Laws (LL.M.) degree, but with the advanced U.S. Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D.) degree. In order to truly appreciate, indeed grapple with, Marxist theory, it must be approached using the educated intellect of one such as Rosa, the glorious light of my life. Marxism, it should go without saying, is neither a prearranged set of Aristotelian first principles (Hebrew, עִקָּרוֹנוּת הַרִאשׁוֹנִים שֶׁל אֲרִיסְטוֹ [MP3], ʿiqqārônūṯ hạ•riʾšôniym šẹl Ăriysəṭô, or Arabic, مَبادِئ أَرِسْطُوطَالِيسِيّ الأُوْلَى [MP3], mabad⫯ī ⫯Aris°ṭūṭālīsiyy ʾal•uw°aỳ) nor merely a formal conglomeration of Kantian postulates (Hebrew, הֲנָחוֹת קַנְטְיָאנִיוּת [MP3], hănāḥôṯ Qạnəṭəyāʾniyūṯ; or Arabic, مُسَلَّمَات كَانْطِيَّة [MP3], musallamāt Kān°ṭiyyaẗ). No, contrary to popular understandings, Marxism is a brilliantly conceived methodology for a full self–realization and collective emancipation from the capitalist world–system (Hebrew, מַעֲרֶכֶת שֶׁל הַעוֹלָמִית הַקָפִּיטָלִיסְטִית [MP3], mạʿărẹḵẹṯ šẹl hạ•ʿôlāmiyṯ hạ•qāpiṭāliysəṯ; or Arabic, نِظَام العَالَمِيّ الرَأْسْمَالِيّ [MP3], nn⫯īẓām ʾal•ʿālamiyy ʾal•r⫯ās°maliyy). Rosa was originally pro–Bolshevik (Russian, на–большевик [MP3], na–Bolʹševik), but she jumped ship after she recognized that the former Soviet Union was becoming an autocracy. As you can see, in the topmost row, the middle and right–hand photos were both apparently taken at the same sitting. You may also click on any of the photographs below to enlarge them:

([German, rote Rosa [MP3]; or Polish, rudy Rosa [MP3]). She was born to Eliasz (Polish for Elijah; MP3) and Liny (Polish; MP3) on March 5ᵗʰ, 1871, in Zamość (Polish [MP3]), Zāʾmŏʾšəṭəś (Yiddish, זָאמֳאשְׁטְשׂ [MP3]), or Zāmôšəṣ′ (Hebrew, זָמוֹשְׁץ׳ [MP3]), Poland (Polish, Polska [MP3]). Rosa was a naturalized German citizen, a libertarian Marxist, a proto–left communist, a doctor of law, and a nonobservant Jew. At only 48 years of age, she then became a secular martyr, after being assassinated by rifle, in Berlin, Germany, on January 15ᵗʰ, 1919. In that very same year, my Jewish father was born—eight months nine days later—on September 24ᵗʰ, 1919, in Brooklyn, New York. Since I was born on February 27ᵗʰ, 1956, Rosa was old enough to be my great grandmother and then some. However, setting that aside, as if she were my wedded wife, I am deeply in love with her. I have, by the same token, happily been a life–long bachelor.

Taking Rosa, the beloved heroine residing eternally in my heart, as exemplar, work heartily, with the spirit of genuine revolutionary fervor, for democratic libertarian communism. Rosa spent hours upon hours working through Capital and other works. She did not treat Marxist primary sources as verbally inerrant (Hebrew, מוּשְׁלָמוּת מִלּוּלִית [MP3], mūšəlāmūṯ millūliyṯ; or Arabic, مَعْصُوم لَفْظِيّاً [MP3], maʿ°ṣūm laf°ẓiyāṇ) or as manna (Hebrew, מָן [MP3], mān; Arabic, مَنّ [MP3], mann; or Common Greek/Hellēniká Koinḗ, μάννα [MP3], mánna, “what is it?”) from heaven. Instead, she approached these sources with the trained mind of a legal scholar. In point of fact, Rosa was one of the few women of her generation with an earned terminal German doctorate in law. That degree is generally considered as higher in prestige than the American Doctor of Jurisprudence (J.D.) degree. In 1963, the J.D. officially supplanted the Bachelor of Laws (LL.B.), which was, quite oddly using U.S. criteria, a second baccalaureate awarded after attaining the Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) or Bachelor of Science (B.S.). The German doctorate is seemingly on par, not with the J.D. or even with the intermediate American Master of Laws (LL.M.) degree, but with the advanced U.S. Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D.) degree. In order to truly appreciate, indeed grapple with, Marxist theory, it must be approached using the educated intellect of one such as Rosa, the glorious light of my life. Marxism, it should go without saying, is neither a prearranged set of Aristotelian first principles (Hebrew, עִקָּרוֹנוּת הַרִאשׁוֹנִים שֶׁל אֲרִיסְטוֹ [MP3], ʿiqqārônūṯ hạ•riʾšôniym šẹl Ăriysəṭô, or Arabic, مَبادِئ أَرِسْطُوطَالِيسِيّ الأُوْلَى [MP3], mabad⫯ī ⫯Aris°ṭūṭālīsiyy ʾal•uw°aỳ) nor merely a formal conglomeration of Kantian postulates (Hebrew, הֲנָחוֹת קַנְטְיָאנִיוּת [MP3], hănāḥôṯ Qạnəṭəyāʾniyūṯ; or Arabic, مُسَلَّمَات كَانْطِيَّة [MP3], musallamāt Kān°ṭiyyaẗ). No, contrary to popular understandings, Marxism is a brilliantly conceived methodology for a full self–realization and collective emancipation from the capitalist world–system (Hebrew, מַעֲרֶכֶת שֶׁל הַעוֹלָמִית הַקָפִּיטָלִיסְטִית [MP3], mạʿărẹḵẹṯ šẹl hạ•ʿôlāmiyṯ hạ•qāpiṭāliysəṯ; or Arabic, نِظَام العَالَمِيّ الرَأْسْمَالِيّ [MP3], nn⫯īẓām ʾal•ʿālamiyy ʾal•r⫯ās°maliyy). Rosa was originally pro–Bolshevik (Russian, на–большевик [MP3], na–Bolʹševik), but she jumped ship after she recognized that the former Soviet Union was becoming an autocracy. As you can see, in the topmost row, the middle and right–hand photos were both apparently taken at the same sitting. You may also click on any of the photographs below to enlarge them:

- Roy Bhaskar (Hindi, राम रॉय भास्कर [MP3], Rāma Rôya Bhāskara), the founder of Bhaskarian critical realism (MP3), developed the underlying metatheory which has been incorporated into this work. In addition, critical realism is a social scientific and philosophical methodology, like all critical theories, for liberating, or emancipating, the individual and, in the specific case of critical realism, for unshackling the planet through libertarian Marxist communism. The objective of critical realism is to absent, or eliminate, all the dialectical absences, such as capitalism and racism, and all of the demireality, or disunity in difference (“dualism”). Replacing these many absences and the realm of demireality, nonduality or advaita (Sanskrit/Saṃskrtam, अद्वैत [MP3]), copresence, the cosmic envelope, or the ground state would flourish. Those are among the major elements of Roy’s Marxist left–libertarianism (Hebrew, לִיבֶּרְטַרְיָנִיזְם הַשְׂמֹאלָנִי [MP3], liybẹrəṭarəyāniyzəm hạ•śəmōʾlāniy; Arabic, اليَسَار مِن لِيبِرْتَارِيَّة [MP3], ʾal•yasār min lībir°tāriyyaẗ; Persian, لِیبِرتَارِیِ گِرَایِیِ چَپ [MP3], líbir°tārí•i girāyí•i čap; Urdu, بَائِیَں آزَادِی [MP3], bā⫯yí ʾâzādí; Guramukhi Punjabi, ਖੱਬੇ ਆਜ਼ਾਦੀਵਾਦ [MP3], khabē āzādīvāda; Shahmukhi Punjabi, کْھبَےَ آزَادِیوَادَ [MP3], ḱ°habē ʾâzādīvāda; Hindi, वाम स्वतंत्रतावाद [MP3], vāma svataṃtratāvāda; or Bengali, বাম উদারনীতিবাদ [MP3], bāma udāranītibāda), and they also provide a vivid illustration of critical realism’s nearly complete incompatibility with Amerocentric so–called right–libertarianism. Bhaskar’s critical realism, through all of his turns (or stages of thinking), are, in effect, brilliant expressions of his developing understandings of rejecting the dialectical absences or demireality of the capitalist system and, through the transformational model of social activity, enabling the dialectical metamorphosis or the copresence of a libertarian communism. He found, in these turns, enhanced ways of expressing many of the same fundamental principles. Transcendental dialectical critical realism—a minor and short–lived turn (2000–2002) which began Bhaskar’s generalized “spiritual turn” and prefaced his final turn—apparently obtained its name from his personal involvement with Transcendental Meditation™. That movement, popularized by the Beatles, was initiated by India’s Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (Hindi, महर्षि महेश योगी [MP3], Maharṣi Maheśa Yogī), 1918–2008. His birth name is unclear. It may have Maheśa Prasāda Varmā (Hindi, महेश प्रसाद वर्मा [MP3]), Maheśa Caṃdra Śrīvāstava (Hindi, महेश चंद्र श्रीवास्तव [MP3]), or some other variation. Moreover, based upon my own original research into Bhaskar’s final turn and the culmination of his overall spiritual turn, the philosophy of metaReality, it was seemingly quite strongly influenced by universal realism. Formulated by India’s Sri Aurobindo (Bengali, শ্রী অরবিন্দ [MP3], Śrī Arabinda; or Hindi, श्री अरविन्द [MP3], Śrī Aravinda), né Aurobindo Ghose (Bengali, অরবিন্দ ঘোষ [MP3], Arabinda Ghōṣa; or rendered into Hindi, अरविंद घोष [MP3], Araviṃda Ghoṣa), 1872–1950, universal realism is discussed in in Book II of Aurobindo’s The Life Divine (see also Book I) and his The Synthesis of Yoga:

In India the philosophy of world–negation has been given formulations of supreme power and value by two of the greatest of her thinkers, Buddha [Sanskrit and Pāli, बुद्ध; MP3, Buddha; Mandarin Chinese/Zhōngguó•Guānhuà, 佛; MP3, Fú; Japanese/Nihongo, 仏; MP3, Futsu; or Korean/Chosŏnmal/Han’gugŏ, 불; MP3, Pul] and Shankara [Sanskrit, शंकर; MP3, Śaṃkara; or शङ्कर; MP3, Śaṅkara] .… The spirit of these two remarkable spiritual philosophies—for Shankara in the historical process of India’s philosophical mind takes up, completes and replaces Buddha,—has weighed with a tremendous power on her thought, religion and general mentality: everywhere broods its mighty shadow, everywhere is the impress of the three great formulas, the chain of Karma [Sanskrit, कर्म; MP3], escape from the wheel of rebirth, Maya [Sanskrit, माया MP3, māyā]. It is necessary therefore to look afresh at the Idea or Truth behind the negation of cosmic existence and to consider, however briefly, what is the value of its main formulations or suggestions, on what reality they stand, how far they are imperative to the reason or to experience. For the present it will be enough to throw a regard on the principal ideas which are grouped around the conception of the great cosmic Illusion, Maya, and to set against them those that are proper to our own line of thought and vision; for both proceed from the conception of the One Reality, but one line leads to a universal Illusionism, the other to a universal Realism,—an unreal or real-unreal universe reposing on a transcendent Reality or a real universe reposing on a Reality at once universal and transcendent or absolute.Sri Aurobindo. The Life Divine. Book II. Pondicherry, India: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department. 2005. Pages 431–432.Already even in the realised higher–mind being and in the intuitive and overmind being the body will have become sufficiently conscious to respond to the influence of the Idea and the Will–Force so that the action of mind on the physical parts, which is rudimentary, chaotic and mostly involuntary in us, will have developed a considerable potency: but in the supramental being it is the consciousness with the Real–Idea in it which will govern everything. This real–idea is a truth-perception which is self-effective; for it is the idea and will of the spirit in direct action and originates a movement of the substance of being which must inevitably effectuate itself in state and act of being. It is this dynamic irresistible spiritual realism of the Truth–consciousness in the highest degree of itself that will have here grown conscient and consciously competent in the evolved gnostic being: it will not act as now, veiled in an apparent inconscience and self–limited by law of mechanism, but as the sovereign Reality in self-effectuating action. It is this that will rule the existence with an entire knowledge and power and include in its rule the functioning and action of the body.Sri Aurobindo. The Life Divine. Book II. Pondicherry, India: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department. 2005. Page 1021.In practice three conceptions are necessary before there can be any possibility of Yoga [Sanskrit, योग; MP3]; there must be, as it were, three consenting parties to the effort,—God, Nature and the human soul or, in more abstract language, the Transcendental, the Universal and the Individual. If the individual and Nature are left to themselves, the one is bound to the other and unable to exceed appreciably her lingering march. Something transcendent is needed, free from her and greater, which will act upon us and her, attracting us upward to Itself and securing from her by good grace or by force her consent to the individual ascension.Sri Aurobindo. The Synthesis of Yoga. Pondicherry, India: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department. 1999. Pages 31–32.By referring to the logic of the Infinite, Sri Aurobindo did not introduce any new element. He reconnected to a central thread that he had been gradually building right from the start. Along with Supermind (the executive agent of the logic of the Infinite), this was the backbone of his “universal Realism.” Its framework allowed him to tackle the problems of human existence from a new perspective. Instead of grappling with the theory of cosmic Illusion, he could now ask what made us “misconceive” or “misapprehend” the Real without denying reality to universal or individual existence.Marcel Kvassay, “Sri Aurobindo’s ‘Universal Realism’ and the Doctrine of Cosmic Illusion.” AntiMatters. Volume 3, number 4, 2009. Pages 83-96.Aurobindo, in his The Life Divine, declares that he has moved from Śaṅkara’s “universal illusionism” to his own “universal realism” …, defined as metaphysical realism in the European philosophical sense of the term.… Aurobindo contends that the great yogī [Sanskrit, योगी; MP3] had a “philosophy of world-negation.”Nicholas F. Gier, Overreaching to be Different: A Critique of Rajiv Malhotra’s Being Different. International Journal of Hindu Studies. Volume 16, number 3, December 2013. Pages 259–285.Whereas the Advaitists [Hindi, अद्वैत के शिष्य; MP3, Advaita ke Śiṣya] and some Buddhists [Mandarin Chinese, 佛陀的门徒; MP3, fútuó•de•méntú; Japanese, 仏陀の弟子たち; MP3, butsuda•no•deshi•tachi; or Hindi, बौद्धों; MP3, Bauddhoṃ] arrived at “a universal Illusionism,” Aurobindo reached “a universal Realism … a real universe reposing on a Reality at once universal and transcendent or absolute.” Totality is real from top to bottom, from pure being to matter. The various planes of being are, as it were, a ladder plunging down from the heights of an absolute supracosmic spirit into lowest matter―perhaps even into planes below matter, although Aurobindo usually assumes that matter is the lowest manifestation of Brahman [Sanskrit, ब्रह्मन्; MP3]. Aurobindo leaves open the possibility of planes of being higher than pure existence, pure consciousness, and pure delight of being, although, again, he usually assumes that these three exhaust the planes of higher being.Troy Wilson Organ, “The Status of the Self in Aurobindo’s Metaphysics: And Some Questions.” Philosophy East and West. Volume 12, number 2, July 1962. 135–151.Click on the photos below for enlargements:

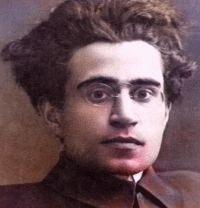

- Antonio Gramsci (Italian/Italiano [MP3]) lived 1891–1937. Although Antifa Autonomism (MP3) or the Autonomist Antifa Movement (MP3) has no clear founder, Gramsci, a courageous political prisoner in Fascist Italy, was certainly a seminal figure. He was an Italian Marxist, a dedicated antifascist, the developer of the theory of cultural hegemony (Hebrew, תֵּאוֹרִית הַהֶגְמוֹנִית הַתַּרְבּוּתִית [MP3], tēʾôriyṯ hạ•hẹḡəmôniyṯ hạ•tạrəbūṯiyṯ; Arabic, نَّظَرِيَّة الهَيْمَنَة الثَقَافِيَّة [MP3], nnazariyyaẗ ʾal•hay°manaẗ ʾal•ṯaqāfiyyaẗ; Persian, تِئُورِیِ هِژِمُونِیِ فَرْهَنْگِی [MP3], t⫯iýuwrí•i hiz°ẖimūní•i far°han°gí; Urdu, ثَقَافَتِی مَحَاصِرْہ کَا نَظَرِیَہ [MP3], ṯaqāfatí maḥāsir°h nazariýah; Guramukhi Punjabi, ਸੱਭਿਆਚਾਰਕ ਸ਼ਾਸਨ ਦੇ ਸਿਧਾਂਤ [MP3], sabhiꞌācāraka śāsana dē sidhānta; or Shahmukhi Punjabi, سَبْھِیَاچَارَکَ شَاسَنَ دَے سِدْھَانْتَ [MP3], sab°hiyāčāraka šāsana dē sid°hān°ta) and the individual who had popularized the term subaltern (MP3; Hebrew, כְּפִיפוּת [MP3], kəp̄iyp̄ūṯ; Arabic, مَرْءُوس [MP3], mar°ˁūs; Persian, اطَاعَت [MP3], ʾaṭāʿat; Urdu, مَاتَحَتَ [MP3], mātaḥata; Guramukhi Punjabi, ਸਬਾਲਟਰਨ [MP3], sabālaṭarana; or Shahmukhi Punhabi, سَبَالَٹَرَن [MP3], sabālaṭarana)―a word redefined by Gramsci for the other, the powerless, or the socially marginalized peoples of the world. Literally speaking, the term, subaltern, refers to secondary. Autonomism (Hebrew, אוֹטוֹנוֹמְיָה [MP3], ʾôṭônōməyāh; Arabic, اِسْتِقْلَالِيَّة الذَاتِيَّة [MP3], ʾis°tiq°lāliyyaẗ ʾal•ḏātiyyaẗ; Persian, خُودْمُخْتَارِی [MP3], ẖūd°muẖ°tārí; Tajik, мухторият [MP3], muẖtoriyat; Urdu, خُودْمُخْتَارِی [MP3], ẖūd°muẖ°tārí; Guramukhi Punjabi, ਆਟੋਨੋਮਿਜ਼ਮ [MP3], āṭōnōmizama; Shahmukhi Punjabi, آٹُونُومِزَمَ [MP3], ʾâṭūnūmizama; or Hindi, स्वायत्तता [MP3], svāyattatā) is an anti–authoritarian and, therefore, an anti–fascist communsm. You may click on each of the images below to enlarge it:

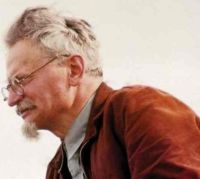

- Hal Draper (1914–1990), born Harold Dubinsky, was among the founders and intellectuals of the early neo–Trotskyist current, third–camp socialism. As a noteworthy aside, Polish American Max Shachtman (Polish, Maks Shakhtman [MP3]), 1904–1972, was also one of the first masterminds behind third–camp socialism. He eventually abandoned his current, leaving the work to his former comrades, and became a social democratic union organizer. Draper himself, a libertarian and heterodox neo–Trotskyist, is credited with coining the term socialism from below (Hebrew, סוֹצְיָאלִיזְם מִלְמַטָה [MP3], sôṣəyāʾliyzẹm mi•ləmạṭāh; Arabic, اِشْتِرَاكِيَّة مِن الأَسْفَل [MP3], ʾiš°tirākiyyaẗ min ʾal•⫯as°fal; Persian, سُوسِیَالِیسْم از پَایِین [MP3], sūsiýālís°m ʾaz paýín; Urdu, ذَیْلَ مَیْں اجِتَمَاعیَاتَ [MP3], ḏaý°la maý°ṉ ʾaǧitamāʿýāta; Guramukhi Punjabi, ਤਲ ਤੋਂ ਸਮਾਜਵਾਦ) [MP3], tala tōṁ samājavāda; or Shahmukhi Punjabi, تَلَ تُوں سَمَاجَڤَادَ [MP3], tala tūṉ samāǧavāda). Other like–minded individuals, coming from a cross–section of Leftist tendencies, have utilized the concept in a similar fashion. Included among them are: Amrit Wilson, Orlando Chirino (MP3), Wayne Price, Dan Swain, Lucien van der Walt (MP3), and Michael Schmidt (MP3). Socialism from below must, by the sheer definition of the phrase, be juxtaposed with the socialism from above (Hebrew, סוֹצְיָאלִיזְם מִלְמַעְלָה [MP3], sôṣəyāʾliyzẹm mi•ləmạʿəlāh; Arabic, اِشْتِرَاكِيَّة مِن الأَعْلَى [MP3], ʾiš°tirākiyyaẗ min ʾal•⫯aʿ°laỳ; Persian, سُوسِیَالِیسْم از بَالَا [MP3], sūsiýālís°m ʾaz bālā; Urdu, اُوْپَرَ سَے اجِتَمَاعیَاتَ [MP3], ʾuw°para sē ʾaǧitamāʿýāta; Guramukhi Punjabi, ਚੋਟੀ ਤੋਂ ਸਮਾਜਵਾਦ, cōṭī tōṁ samājavāda [MP3]; or Shahmukhi Punjabi, چُوْٹِی تُوں سَمَاجَڤَادَ [MP3], čūṭí tūṉ samāǧavāda) which, simultaneously, monopolized and wreaked havoc upon the 20ᵗʰ century. Alliance for Workers’ Liberty, ZCommunications, Center for Economic Research and Social Change (which publishes the International Socialist Review), International Organization for a Participatory Society, International Socialist Organization, and New Politics comprise a cursory selection of organizations and publications that have expressed their advocacy for a libertarian socialism from below. The following is a compilation of quotations on that subject:

… the tendency [Max] Shachtman founded continued, and a group of his co–thinkers (including [Hal] Draper, Phyllis and Julius Jacobson, Herman Benson, and others) continued to develop “third camp” politics as a heteredox, broadly–libertarian Trotskyism which emphasised working–class independence and democracy. The third campists had an attitude on the “party question” which no doubt also offends Workers Power’s sensitivities, emphasising debate and dissent, and the rediscovery of the classical–Bolshevik view that internal disagreements should be argued through as publicly as possible, rather than compelling members to lie about their opinions in public. That is indeed the tradition with which Workers’ Liberty identifies. Identifying with the political tradition Max Shachtman helped develop in no way compels us to apologise for choices he made later on. Against the Shachtman of the mid–1950s, we side with Draper, the Jacobsons, and others, who continued in revolutionary politics until the end of their lives.Ira Berkovic, “A note on ‘(neo–)Shachtmanism.’” Workers’ Liberty: Reason in Revolt. The Alliance for Workers’ Liberty. 2017. No pagination.… the following pages propose to investigate the meaning of socialism historically, in a new way. There have always been different ‘kinds of socialism,’ and they have customarily been divided into reformist or revolutionary, peaceful or violent, democratic or authoritarian. etc. These divisions exist, but the underlying division is something else. Throughout the history of socialist movements and ideas, the fundamental divide is between Socialism–From–Above and Socialism–From–Below.What unites the many different forms of Socialism–from–Above is the conception that socialism (or a reasonable facsimile thereof) must be handed down to the grateful masses in one form or another, by a ruling elite which is not subject to their control in fact. The heart of Socialism–from–Below is its view that socialism can be realized only through the self–emancipation of activized masses in motion, reaching out for freedom with their own hands, mobilized from below” in a struggle to take charge of their own destiny, as actors (not merely subjects) on the stage of history. “The emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves”: this is the first sentence in the Rules written for the First International by [Karl] Marx, and this is the First Principle of his life–work.Hal Draper. The Two Souls Of Socialism. Revised edition. Berkeley, California: Independent Socialist Committee—A Center for Socialist Education. 1966. Pages 3–4.… in the second half of the nineteenth century, “socialist” came to signify not merely concern with “the social question,” but opposition to capitalism and support for some variety of social ownership of the means of production. So, while never abandoning the term “communist,” [Karl] Marx and [Friedrich] Engels also became quite happy to call themselves socialists. What is most distinctive about the kind of socialism that they supported, however, is that it can only be created through the active participation of workers themselves. The American Marxist Hal Draper called this conception “socialism from below” and contrasted it with various varieties of “socialism from above” .… Historically, most versions of self-described socialism—including both Stalinism and social democracy—have been varieties of “socialism from above,” which from [Karl] Marx and [Friedrich] Engels’ perspective was not genuine socialism at all.Utopianism was elitist and anti democratic to the core because it was utopian—that is, it looked to the prescription of a prefabricated model, the dreaming–up of a plan to be willed into What unites the many different forms of Socialism–from–Above is the conception that socialism (or a reasonable facsimile thereof) must be handed down to the grateful masses in one form or another, by a ruling elite which is not subject to their control in fact. The heart of Socialism–from–Below is its view that socialism can be realized only through the self-emancipation of activized masses in motion, reaching out for freedom with their own hands, mobilized from below” in a struggle to take charge of their own destiny, as actors (not merely subjects) on the stage of history. “The emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves”: this is the first sentence in the Rules written for the First International by [Karl] Marx, and this is the First Principle of his life–work.Hal Draper. The Two Souls Of Socialism. Revised edition. Berkeley, California: Independent Socialist Committee—A Center for Socialist Education. 1966. Pages 8–9.[Karl] Marx and [Friedrich] Engels also became quite happy to call themselves socialists. What is most distinctive about the kind of socialism that they supported, however, is that it can only be created through the active participation of workers themselves. The American Marxist Hal Draper called this conception “socialism from below” and contrasted it with various varieties of “socialism from above,” in which an elite imposes change on a passive working class. Historically, most versions of self-described socialism—including both Stalinism and social democracy—have been varieties of “socialism from above,” which from Marx and Engels’ perspective was not genuine socialism at all.Phil Gasper, “Reviving socialism from below: Capitalism’s biggest crisis since the 1930s raises the question of what can replace it.” International Socialist Review. Issue 65, May 2009. No pagination.Socialist and democratic developed from below through a gradual and often slow process of education and discussion. In this way, land was redistributed to women and people of previously oppressed groups who never before had a right to this means of survival. Oppressive feudal marriage laws were changed to give women more power.Amrit Wilson, “Socialism from below.” New Statesman & Society. Volume 4, number 154, June 1991. Page 10.… [An] important issue is the role of social classes in this revolution. You don’t have to refer to [Karl] Marx, [Friedrich] Engels, [Vladimir] Lenin, or [Leon] Trotsky to know that the only way to overturn capitalism, a system in which a minority imposes its will on the majority, is that the working class and the people, we who are the majority and the producers, take the lead in expropriating the enterprises and place them under our control. In that sense, what we mean by socialism is very simply stated.Orlando Chirino, “Venezuela’s PSUV and Socialism from Below: Interview with Orlando Chirino.” New Politics. Volume 11, number 4, winter 2008. Pages 17–22.The dominant trend in socialist thought during this period, then, was a new variant of socialism from above. The struggle of working class people to create new institutions of popular democratic control was seen as having little or nothing to do with the creation of a socialist society. Instead, elected socialist officials would simply take over the existing bureaucratic structures of society and run them more humanely. Rather than a qualitatively different society, socialism was depicted as a gently improved form of the existing social order. Yet, despite the wide influence of this doctrine, some Marxists remained committed to the idea of socialism from below. The most important of these was the Polish revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg.…… [The] upsurge in militant working class activity powerfully influenced the thinking of some radical writers and organisers. A few of them began to think of the working class as the group that could change society. Indeed, some theorists began to talk in terms of the working class liberating itself through its collective action. Notable in this regard was the French revolutionary Flora Tristan, who linked together ideas of working class self-emancipation and women’s liberation with the proposal for a world-wide organisation of workers. But it was in the writings and the organising of a German socialist, Karl Marx, that the working class took centre stage in socialist thought. Inspired by the emergence of this class, [Karl] Marx developed a wholly new socialist outlook based upon the principle of socialism from below.David McNally. Socialism from Below. Chicago, Illinois: International Socialist Organization. 1986. Ebook edition.Today … state–Communism has been relatively discredited with the fall of the Soviet Union and the turn of the Chinese state to open capitalism. As a consequence, the concept of socialism-from-below has become widely attractive to many radicals. However, the concept of socialism–from–below, at least as raised by [Hal] Draper and by [David] McNally (at least until his most recent book), has been used ambiguously. Contrary to the views of the anarchists, these writers claim that Marxism is most consistent with revolutionary socialism–from–below, and that anarchism is an example of authoritarian socialism. I will argue instead that the divide between authoritarian and libertarian–democratic tendencies runs through (inside) Marxism as well as through anarchism. However, I believe that, while there is value in Marxism, overall, anarchism is most consistent with the development of a liberating socialism–from–below.Wayne Price, “Socialism from Above or Below.” The Utopian. Volume 3, 2002. Pages 75–85.]I have been an anarchist–pacifist (influenced by Paul Goodman and Douglas Macdonald), a Trotskyist (a variety of Marxist), and am now an socialist–anarchist of the class struggle, pro–organization (“Platformist”), trend. I identify with the revolutionary tradition of anarchist–communism. Through all these incarnations, I have remained a libertarian socialist and a believer in socialism–from–below.Wayne Price. The Abolition of the State: Anarchist & Marxist Perspectives. Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse. 2007. Page 8.I remain an anarchist, a decentralist socialist, and a believer is socialism–from–below. As a class struggle, Platformist, revolutionary anarchist, I can have all the benefits I sought as a Trotskyist, while maintaining the libertarian vision of anarchism. I no longer advocate a “workers’ state” (whatever that means), but I do advocate a federation of workers’ and popular councils (in the tradition of the Friends of Durruti Group of the Spanish revolution). I no longer advocate a vanguard (Leninist) party, which aims to rule over the workers, but I do advocate a revolutionary organization of anachist workers: Platformism or especificismo. (These topics are discussed in essays in this book as well as in my book, The Abolition of the State: Anarchist and Marxist Perspectives.) While I no longer call myself a Marxist, I accept many ideas from the Marxist tradition (as can be seen from my essays) This is especially true from the libertarian Marxists (such as C.L.R. James, the council communists, etc.). I now regard myself as a Marxist–informed anarchist. I have joined the Northeastern Federation of Anarchist–Communists (or NEFAC) and write for the www.Anarkismo.net site, which is the web site for our international tendency.Wayne Price. What I Believe and How I Came to Believe It. Berkeley, California: The Anarchist Library imprint of Open Guild Organization. 2008. Page 6.If socialism is just about taking control of the existing state, it is understandable that many are suspicious of it. But socialism from below implies a different approach. It argues that the institutions of the state are structured in a way that denies popular control. Alongside the formally ‘democratic’ pieces of the state – where those exist – are a series of hierarchically organised bodies, the police, army, judiciary, civil service etc., that limit the space for democracy. These are a block on the possibility of extending democratic control in society. These institutions must be removed and replaced.…If socialism from below is to mean anything today, it is as a guiding thread that runs through our political practice, one that constantly reminds us to ask whether and how what we do empowers people to become agents of their own emancipation. To achieve this truly would be ‘doing politics differently’ – differently from the capitalist parties, broken social democracy, and, sadly, so many revolutionary groups that have gone before. The devil, as ever, is in the detail; but no one said it was going to be easy.Dan Swain, “Socialism from Below.” New Politics. July 17ᵗʰ, 2015. Online publication. No pagination.… [One] arena where socialism from below matters is the question of democracy. There has historically been, and to a certain extent there still is, a way of talking about socialism as being concerned first and foremost with material comfort and a more equal distribution of wealth and resources. To the extent that democracy fits into this it is often as an optional extra, a “good thing,” but not strictly part of the picture. Socialism from below rejects this, and re-asserts democracy as an integral part of socialism. Socialism from below follows from a commitment to democracy in socialism in the following way: If your goal is just material comfort, or a better distribution of resources, you don’t need mass participation. You don’t need to involve, engage and mobilize a movement. Or rather, you do, but only temporarily, only in order to back up demands and policies, put pressure on those in power. If, on the other hand, your goal is a society in which the overwhelming majority are capable of participating in the running of society, you have to be concerned with empowering them to do so, and this empowerment requires a level of democracy.Dan Swain, “Socialism still comes from below.” Socialist Worker. July 16ᵗʰ, 2015. Online publication. No pagination.The common idea – ‘socialism from below’ – is … widely shared.The Socialist Workers Party, in spite of its own obviously Stalinist internal regime, also subscribes to that idea, and its Greek co-thinkers use the tag as the title of their bimonthly journal.…I have said that the SWP [Socialist Workers Party] subscribes to ‘socialism from below’ in spite of its own obviously Stalinist internal regime, but in fact it is arguable that such a regime follows from the conception of ‘socialism from below’ as interpreted by the SWP, by its co-thinkers and its ex-members.Mike Macnair, “Socialism from below: a delusion.” Weekly Worker. Issue 1071, August 2015. Online publication. No pagination.We [the New Left] also challenged the prevailing view that the so-called affluent society would of itself erode the appeal of socialist propaganda—that socialism could arise only out of immiseration and degradation. Our emphasis on people taking action for themselves, “building socialism from below” and “in the here and now,” not waiting for some abstract Revolution to transform everything in the twinkling of an eye, proved, in the light of the re-emergence of these themes after 1968, strikingly prefigurative.Stuart Hall, “Life and Times of the First New Left.” New Left Review. Series II, number 61, January–February 2010. Pages 177–196.… I will analyze the ways in which the themes in my conception of socialism–from–below appear (or are ignored) in analyses of the Occupy movement. By examining its key discussions, I intend to situate Occupy within the Infrastructure of Dissent and [Rosa] Luxemburg’s theories on social transformation through mass mobilization. By situating Occupy within these theories, I will offer a refreshed look at the opportunities and obstacles facing leftist struggle in our time, in order to gain a better grasp upon how mass movements might bring us closer to realizing a society of socialism–from–below.Holly Campbell. Building Socialism From Below: Luxemburg, Sears, And The Case Of Occupy Wall Street. Major research paper for Master’s in Social Justice and Community Engagement. Wilfrid Laurier University. Brantford, Ontario. 2014. Page 34.The Challenge: Defining a Socialism from Below …The crippling contradiction at the heart of Bolshevism lies between its central defining images of modernity and its socialist politics and culture. The former entail a theory of productive forces and of the economic superiority of capitalist methods; the latter calls for increasingly conscious, collective, and egalitarian self–assertion from below. The contradiction is an antagonistic one: to choose either horn of the dilemma is to undercut the basis of the other. Bolshevism certainly broke the automatic link between level of productive forces and socialist revolution.Philip Corrigan, Harvie Ramsay, and Derek Sayer, “Bolshevism and the USSR.” New Left Review. Series I, number 125, January–February 1981. Pages 45–60.For anarchists, individual freedom is the highest good, and individuality is valuable in itself, but such freedom can only be achieved within and through a new type of society. Contending that a class system prevents the full development of individuality, anarchists advocate class struggle from below to create a better world. In this ideal new order, individual freedom will be harmonised with communal obligations through cooperation, democratic decision-making, and social and economic equality. Anarchism rejects the state as a centralised structure of domination and an instrument of class rule, not simply because it constrains the individual or because anarchists dislike regulations. On the contrary, anarchists believe rights arise from the fulfilment of obligations to society and that there is a place for a certain amount of legitimate coercive power, if derived from collective and democratic decision-making.Lucien van der Walt and Michael Schmidt, “Socialism from Below: Defining Anarchism,” in Lucien van der Walt and Michael Schmidt. Black Flame: The Revolutionary Class Politics of Anarchism and Syndicalism. Oakland, California: AK Press. 2009. Pages 33–82.Perhaps surprisingly, he [Hal Draper] excludes anarchism from the camp of socialism from below. Its affirmation of absolute individual liberty logically leads to the right of individuals to impose their own tyranny on others, even on the majority. ‘It is the other side of the coin of bureaucratic despotism, with all its values turned inside–out, not the cure or the alternative.’ His argument is based on the founders of theoretical anarchism, and he undoubtedly has a case as he dissects their writings. [Pierre–Joseph] Proudhon, in particular, was a convinced sexist and racist, an opponent of trade unions, and a cheerleader for dictators when he wasn’t eying up their position for himself.Aindrias Ó Cathasaigh, “Hal Draper, The Two Souls of Socialism.” Red Banner. Volume 48, June 2012. Pages 1–4.Before the October Revolution, [Vladmir] Lenin saw “workers’ control” purely in terms of “universal, all-embracing workers’ control over the capitalists.” He did not see it in terms of workers’ management of production itself (i.e. the abolition of wage labour) via federations of factory committees. Anarchists and the workers’ factory committees did. On three occasions in the first months of Soviet power, the factory committees sought to bring their model into being. At each point the party leadership overruled them. The Bolshevik alternative was to vest both managerial and control powers in organs of the state which were subordinate to the central authorities, and formed by them. Workers’ management from below was not an option. Lenin himself quickly supported “one–man management” invested with “dictatorial powers” after “control over the capitalists” failed in early 1918. By 1920, [Leon] Trotsky was advocating the “militarisation of labour” and implemented his ideas on the railway workers.Anonymous. The Anarchist Alternative to Leninism: Socialism from Below? Berkeley, California: Anarchist Zine Library imprint of Open Guild Organization. 2001. (From a leaflet distributed at “Marxism 2001” in London, one of the annual conferences coordinated by the British Marxist–Leninist–Trotskyist organization, the Socialist Workers Party.) No pagination.In the case of co–management [in Venezuela], this also can be due to diverging understandings and expectations. While workers usually see it as an intermediate step toward workers’ control and the construction of a new socialism from below, many officials see it more as a mechanism for reducing conflict at work and improving the processes, thus taking advantage of the labour force’s subjectivity without allowing it true participation. This experience has also been repeated in the creation of the Socialist Workers’ Councils (CST) in state enterprises and institutions since 2008. The deeper the process of change and/or popular mobilisation, the greater the contradictions. Conflicts over comanagement and problems in its practice emerged especially in the firms taken over and expropriated, and in state enterprises where there was a worker initiative for more workers’ participation or control. The first two businesses to be expropriated – the paper factory Invepal and the valve factory Inveval, both of which had been taken by the workers – exemplify this situation, as does the case of the state aluminium smelter Alcasa.Dario Azzellini. Communes and Workers’ Control in Venezuela: Building 21ˢᵗ Century Socialism from Below. Ned Sublette, translator. Leiden, the Netherlands, and Boston, Massachusetts: Leiden. 2017. Page 174.The traditional Left continues to hamstring itself with fantasies of salvific sweeps, a position that derides everything beyond mass action as insufficient or reformist. The claim that “socialism in one city is impossible” may or may not be worth talking about at one level, but at another it is exactly the all–or–nothing acid that dissolves radical thinking and action, and at still another level is just plain untrue. Just as the construction of a new solidarity economy has to be built piecemeal from the ruins of late capitalism, so too might emerge a commonwealth, with some old, some new, some repurposed elements, from workplace to workplace, neighborhood to neighborhood.Socialism, or any other rendition of radically egalitarian and/or utopian social relations, will wax and wane, swell and subside, be fought over and defended, built and rebuilt. If we perceive the commonwealth as an artifactualized thing that we either have or we don’t, then we’re doomed to an endless loop of disappointment and recrimination. The commons, or a socialism from below, or a radically democratic pluralistic altermodernity, or whatever, has to be understood not as a secular-socialist heaven, but as a horizon that keeps bending at the edges, a build-the-road-as-we-travel ongoing act of emergence.Matt Hern. A What a City Is For: Remaking the Politics of Displacement. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. 2016. Ebook edition.In his youth, [Karl] Polanyi had been fleetingly attracted to anarchism and varieties of socialism “from below,” but in the bearpit of Russia’s socialist factions he backed those who maintained that socialism could only be achieved following a lengthy stage of capitalism against those who supposed that a global socialist transformation could begin on Russian soil, and his post-1917 trajectory was via guild socialism toward social democracy, a comparatively patrician current that in several respects – notably its advocacy of nationalism and state-led social engineering – resembled the new edition of communism that was emerging in late 1920s Russia. For Polanyi, socialism was defined by two principal claims. One was for workers’ control of production. This would have precluded him from defining [Joseph] Stalin’s Russia as socialist were it not for his propensity to conflate the labour movement with what he held to be its political organisations. Thus, he justified his acceptance of the CPSU [Communist Party of the Soviet Union] as a representative of Russian labour by the assumption that it was devoted to the “democratic control of industry.” The other claim was that a socialist economy is by definition geared to “the maximum development of the means of production” combined with a socially just distribution of the product. In Russia, the Five-Year Plans were visibly producing “the enrichment” of Soviet territory, and, with some creative accounting and a willingness to disbelieve journalistic reports of gaping class divisions, the “just distribution” criterion appeared to be met too. Consequently, Polanyi could marvel at the achievements of Soviet Russia, including industrialisation and collectivisation. Although these led to “severe suffering for the masses,” he justified this in terms of the putative intention – to ameliorate poverty – and the “spectacular” and “admirable growth rate” that they enabled. They had, he maintained, proved ‒the possibility of socialist economics on a large scale,– and, paradoxical though this sounds, had also demonstrated the unassailable truth of marginalist economics. The evidence was there for the world to see: “Russia, which ten years ago was of no account as an industrialised country, ranks now amongst the very first. Socialism has been established in one country.” Though temporarily restricted to one country, Stalin’s regime cast a bright light on the future of humanity as a whole.Gareth Dale. Reconstructing Karl Polanyi: Excavation and Critique. London: Pluto Press. 2016. Pages 82–83.Photographs of Draper are immediately below. Those on the left and the right were, apparently, both taken at the same venue. The second row of pictures—including the one on the left which was colorized by me—are of Shachtman. Click on any of them for enlargements:

- Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw (born 1959), a brilliant American law professor at both Columbia University and University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), developed intersectionality or intersectional theory (MP3; Hebrew, תֵּאוֹרְיוּת הַהִצְטַלְּבוּת [MP3], tēʾôrəyūṯ hạ•hiṣəṭạlləḇūṯ; Arabic, نَظَرِيَّة التَقَاطُعَات [MP3], naẓariyyaẗ ʾal•taqāṭuʿāt; Persian, نَظَرِیَهِ مُتْقَاطع [MP3], naẓariýah•i mut°qaṭʿ; Urdu, اِنْتِبَاہَ نَظَرِیَہَ [MP3], ʾin°tibaha naẓariýýaha; Guramukhi Punjabi, ਇੰਟਰਸੈਕਸ਼ਨਾਂ ਦੇ ਥਿਊਰੀ [MP3], iṭarasaikaśanāṁ dē thiꞌūrī; or Shahmukhi Punjabi, اِنٹَرَسِیکَسَنَاں دَے تھِیُورِی [MP3], ʾin°ṭarasíḱasanaṉ dē t°hiýūrí). Using the metaphor of intersections on a roadmap, she presents a multidimensional approach to domination. Rather than treating oppression as a tangible, oppression is considered relationally and contextually. A person might occupy the status of an oppressor in one structure and the status of an oppressed person in another. In effect, intersectionality demonstrates the complex contradictions in the capitalist system. Crenshaw’s theory expands capitalist studies beyond a narrow and simplistic economism, or economic determinism, to include diverse substructures of modernity. In both cases, the amplification is clear from the perspectival designations themselves. If capitalism is correctly regarded as intersecting traffic flowing from multiple directions—a dynamic elucidation of communist internationalism—perhaps merely delineating an economy, or even a political economy, would offer an insufficient portrayal of reality. If, on the other hand, capitalism is an intersection—like a prison cell, a roadmap, a spider’s web, or a birdcage—then capitalism must be approached multidimensionally, not as a two–dimensional flatland. Due to the contradictions of capitalism, one may experience power, privilege, wealth, and prestige in certain areas of life, yet not in others. For example, I lived in Southern Appalachia for four years―Wise, Virginia. It is a poor, dying coal mining area. Yes, it is poor; and yes, it is mostly white. However, it is poor because of a lack of good–paying jobs. It is mostly white because that part of the South did not have plantations. Continuing poverty does not attract new people, including minorities, to move in. That is the value of intersectional theory. Yes, they are white. Yes, they are in a poor region. They are poor because of their region, not because they are white. Race has no direct relation to their poverty. Southern Appalachia and the Mississippi Delta are the two poorest regions of the U.S. but for different historical reasons. Click on any of the pictures below for an enlargement:

- Patricia Hill Collins, born in 1948, is “Distinguished University Professor Emerita” at the University of Maryland. She was, in addition, the first African American woman to be honored with the presidency of the American Sociological Association in 2009. Collins introduced Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw’s intersectionality into the field of sociology. In the process, Collins inevitably added her own original modifications to this critical theory, including the matrix of domination (Hebrew, מַטְרִיצָה שֶׁל הַשְׁלִיטָה [MP3], mạṭəriyṣāh šẹl hạ•šəliyṭāh; Arabic, مَصْفُوفَة الهَيْمَنَة [MP3], maṣ°fūtaẗ ʾal•hay°manaẗ; Persian, مَاتْرِیکْسِ سُلْطَه [MP3], māt°ríḱ°s•i sul°ṭah; Urdu, تَسَلُّط کَا مَیٹْرِکْس [MP3], tasalluṭ ḱā mēṭ°riḱ°s; Guramukhi Punjabi, ਜ਼ੁਲਮ ਦੇ ਸਰੋਤ [MP3], zulama dē sarōta; or Shahmukhi Punjabi, زُلَمَ دَی سَرُوتَ [MP3], zulama dē sarūta)—the sources of oppression—and the two–stage methodology of, first, shifting the center of one’s thinking to the socially marginalized or “the other” and, second, reconstructing knowledge based upon having shifted the center. Her qualitative sociological research method can be regarded as a unique approach to feminist standpoint epistemology (Hebrew, אֶפִּיסְטֶמוֹלוֹגְיָה הַבְּחִינָה הַפֶמִינִיסְט [MP3], ʾẹpiysəṭẹmôlōḡəyāh hạ•bəḥiynāh hạ•p̄ẹmiyniyiysəṭ; Arabic, نِسْوِيَّة المَعْرِفَة الوُجْهَة [MP3], nis°wiyyaẗ ʾal•maʿ°rifaẗ ʾal•wuǧ°haẗ; Persian, مَعْرِفَتِ شَنَاسِیِ دِیدْگَاهِ فِمِینِیسْتِی [MP3], maʿ°rifat•i šanāsí•i díd°gāh•i fimínís°tí; Urdu, نَسَائِی نُقْطَہ نَظَرَ عِلمَ کِی اصَلَ [MP3], nasā⫯yí nuq°ṭah naẓara ʾilma ḱí ʾaṣala; Guramukhi Punjabi, ਨਾਰੀਵਾਦੀ ਦ੍ਰਿਸ਼ਟੀਕੋਣ ਗਿਆਨ [MP3], nārīvādī driśaṭīkōṇa giꞌāna; or Shahmukhi Punjabi, نَارِیوَادِی دْرِشَٹِیکُونَ گِیَانَ [MP3], nārívādí d°rišaṭíḱūna giýāna) or, more broadly, to standpoint epistemology in general. It is a recognition that an awareness of oppression varies according to one’s relational perspective. Indeed, intersectional theory commonly includes standpoint epistemology, but the reverse is not as frequently the case. I once, just as an aside, served on a panel at a sociological conference with Collins. Please click on any of the three images below for enlargements:

- Stateless British resident Tony Cliff (1917–2000) was born in Palestine (Arabic, فِلَسْطِين [MP3], Filas°ṭīn; Hebrew, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה [MP3], Pālẹśətiynāh; Persian, فِلَسْطِین [MP3], Filas°ṭín; Urdu, فِلَسْطِینَ [MP3], Filas°ṭína; Shahmukhi Punjabi, فَلَسَتِينَ [MP3], Falasatína; or Guramukhi Punjabi, ਫਲਸਤੀਨ [MP3], Phalasatīna) three decades before the establishment of Israel (Hebrew, יִשְׂרָאֵל [MP3], Yiśərāʾēl; Arabic, إِسْرَائِيل [MP3], ⫰Is°rā⫯yīl; Persian, اِسْرَائِيل [MP3], ʾIs°rā⫯yíl; or Urdu, اِسْرَائِيلَ [MP3], ʾIs°rā⫯yíla; Shahmukhi Punjabi, عِزَرَائِیلَ [MP3], ʿIzarā⫯yíla; or Garumukhi Punjabi, ਇਜ਼ਰਾਈਲ [MP3], Izarāꞌīla) by the United Nations. He developed a post–Trotskyist tendency called international socialism. Cliff’s birth name was Yigael Gluckstein or Ygael Gluckstein (Hebrew, יִגְאָל גְּלוּקְשְׁטָיִין [MP3], Yiḡəʾāl Gəlūqəšəṭāyiyn; my Arabization/taʿrībuṇ (Arabic, تَعْرِيْبٌ [MP3]), يِيجْأَل غْلُوْكْشْطَايّْن [MP3], Yīġ⫯āl Ġ°lūk°š°ṭāyy°n; or my Persianization/Fār°sí•i šudan/(Persian, فَارْسِیِ شُدَن [MP3]), یِیگأَل گْلُوکْشْْطَایّْن [MP3], Ýíg⫯āl G°lūḱ°š°ṭāýý°n). Unfortunately, Cliff, who referred to himself as a Luxemburgist for quite some time, suddenly abandoned that label. Some of his members, annoyed at him over this issue, continued referring to themselves by that designation. Cliff, moreover, popularized the term, “state capitalism,” when referring to the former Soviet Union. Nevertheless, the issue, while perhaps of historical interest, is, in terms of current affairs, irrelevant. Mainland China has become an authoritarian capitalist state, while the Russian Federation is a right–wing crony capitalist state. You may click on each of the below photos for an enlargement:

- American Richard D. Wolff’s (born 1942) proposes workers’ self–directed coöperative enterprises (Hebrew, מִפְעָלִי שִׁתּוּף פְּעֻלָּה שֶׁל הַעוֹבֵדִים [MP3], mip̄əʿāliy šitūp̄ pəʿullāh šẹl hạ•ʿôḇēḏiym; or Arabic, مُؤَسَّسَات المُتَعَاوِنَة الذَاتِيَّة المُوَجَّهَة لِلعُمَّال [MP3], m⫯uwassāt ʾal•mutaʿāwinaẗ ʾal•ḏātiyyaẗ ʾal•muwaǧǧahaẗ lil•ʿummāl). On the other hand, I was disappointed when, in 2016, he supported the presidential candidacy of a social democrat, U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders, and repeatedly referred to him, erroneously by standard academic criteria, as a socialist. Why would a communist do that? Although completely irrelevant to the subject at hand, to quote Yul Brenner’s character in the disturbingly Americocentric movie, The King and I, Wolff’s campaigning, or effective campaigning, for Sanders was, from my perspective, a “puzzlement.” Sanders did more harm to socialism than the most rabid right–winger. Due to his popularity, I only refer to myself as a communist these days, never as a socialist. Meanwhile, a generation of social democrats now defines itself as socialist. Click on any of Wolff’s pictures for enlargements:

- Titoism is the aggressive and, indeed, courageous response to Stalinism ( Hebrew, סְטָלִינִיזְם [MP3], Səṭāliyniyzəm; or Arabic, سْتَالِينِيَّة [MP3], S°tāliniyyaẗ) by Yugloslav Marshal Josip Broz Tito (Serbian/Srpski, Маршал Јосип Броз Тито [MP3], Maršal J̌osip Broz Tito), 1892–1980. Although once a Titoist, I am no longer a proponent of market socialism, including Tito’s version, in general. Nevertheless, I still admire Tito’s dedication to building worker coöperatives. In my opinion, Tito came more proximate to the Marxist first stage of communism than any other head of state in the 20ᵗʰ century. Click on each of the pictures below for an enlargement:

- De Leonism (MP3), created by U.S. pre–Bolshevik (Russian/Rossiâne, пред-Большевик [MP3], pred–Bolʹševik) activist Daniel De Leon (MP3), 1852–1914, is a sensible (and libertarian Marxist) approach to syndicalism (MP3). Click on any of De Leon’s three pictures for enlargements:

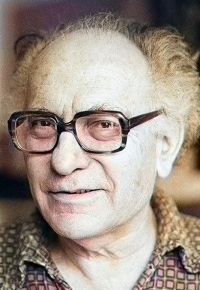

- Immanuel Wallerstein (MP3), born in 1930, was the originator of world–systems analysis (Hebrew, נִתּוּחַ הַמַעֲרֶכוּת שֶׁל הַעוֹלָם [MP3], nitūhạ hạ•mạʿărẹḵūṯ šẹl hạ•ʿôlām; Arabic, تَحْلِيل مِن الأَنْظِمَة العَالَمِيَّة [MP3], taḥ°līl min ʾal•⫯an°ẓimaẗ ʾal•ʿālamiyyaẗ; Persian, تَجْزِیِه وَ تَحْلِیلِ سِیسْتِمِ هَایِ جَهَانِی [MP3], taǧ°ziýih va taḥ°líl•i sís°tim•i hāý•i ǧahāní; Urdu, عَالَمِی نِظَامَ تَجزِیِہ [MP3], ʿālamí niẓāma taǧ°ziýih; Guramukhi Punjabi, ਵਿਸ਼ਵ ਪ੍ਰਣਾਲੀ ਵਿਸ਼ਲੇਸ਼ਣ [MP3], viśava praṇālī viśalēśaṇa; or Shahmukhi Punjabi, وِشَوَ پْرَنَالِی وِشَلَیشَنَ [MP3], višava p°ranālí višalēšana). I have found conceiving of capitalism as a world–system to be extremely helpful in my work. Capitalism is a global, not only a national, political economy. You may click on any of the below images for an enlargement:

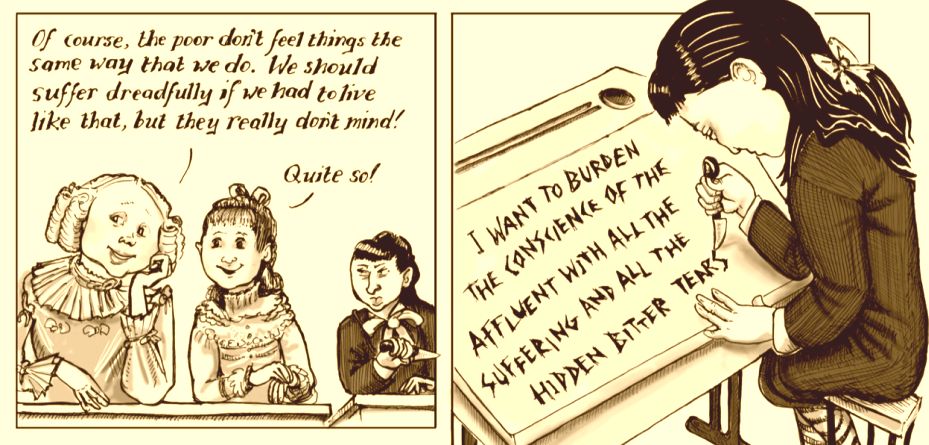

- The virtuous and courgeous Audre Lorde (1934–1992), pen name of Audrey Geraldine Lorde, famously wrote, “The true focus of revolutionary change is never merely the oppressive situations we week to escape, but that piece of the oppressor which is implanted deep within each of us.” Lorde helped many of us to appreciate her deep understandings of false consciousness and class consciousness. Click on any of the three images to enlarge it:

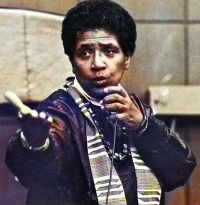

- Cesar Chavez (Spanish/Español, César Chávez [MP3]), 1927–1993, substantially introduced me to the New Left, in 1968, through his leadership of the United Farm Workers of America. I distributed petitions, along with other members of the Students’s Democratic Coalition, for people to sign pledges to boycott California grapes, in solidarity with the Mexican migrant workers. As we distributed the petitions to willing supermarket shoppers, an unknown man came by and copied down all of our names. Not knowing any better, being just twelve years old, I politely gave him my name. Obviously, I should have simply declined, but the thought never even occurred to me. Somewhere, buried in a file, there is most likely a record in Washington, D.C., of my activism that day. Click on any of the pictures for an enlargement:

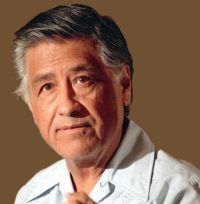

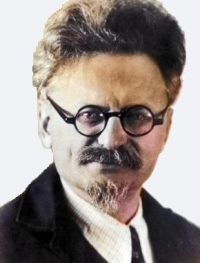

- Leon Trotsky (Russian, Лео́н Тро́цкий, León Tróckij [MP3]), born Lev Davidovich Bronstein (Russian, Лев Давидович Бронштейн [MP3], Lev Davidovič Bronštejn), lived 1879–1940. Through the work of Tony Cliff and Max Shachtman, Trotsky gave a heart to my communism, and, after abandoning Titoism, I became a Trotskyist in two distinct flavors: First, Tony Cliff’s International Socialism and, then later, Hal Draper’s libertarian version of Third–Camp Socialism. By the same token, while recognizing that Lev was waging a war, I was, to be blunt, not a big fan of his authoritarianism. They, admittedly, mellowed while traveling within the United States and, later, in exile in Mexico. Trotsky appears to have moved in a more libertarian direction, including with his informality and apparent egalitarianism. Moreover, during his North American travels, he was on the run for his life. Trotsky was subsequently assassinated in Mexico. The weapon of choice was a simple icepick. It, obviously, left no fingerprints, and DNA testing was, sadly, not yet available. Substantively, Trotsky’s astute analysis of American racism corresponds with mainstream sociological usage. He brilliantly utilized the example of the Southern plantation system. Trotsky certainly had his rhetoric on an international revolution to spread communism. Joseph Stalin (Georgian/Kartuli Ena, იოსებ სტალინი [MP3], Ioseb Stʼalini; or Russian, Иосиф Сталин [MP3], Iosif Stalin) had his own rhetoric, too, but he never carried out what he claimed in advance. Rhetoric, no matter how eloquent, is not a good predictor of social action. You can never know what a politician will do until they are in power. Rosa Luxemburg discerningly critiqued Lev’s authoritarian methods as well as his formulaic approach to communism. In the visionary world of dreams, Red Rosa knocked at the door of my heart. I was prepared for her. Click on any of the three pictures of Trotsky below for enlargements: